Sponges feed primarily by collecting suspended particles from water pumped through internal canal systems. Water enters canals through a multitude of tiny incurrent pores in the outer layer of cells, a pinacoderm. Incurrent pores, called dermal ostia, have an average diameter of 50 µm. Inside the body, water is directed past the choanocytes, where food particles are collected on the choanocyte collar. The collar is made of many fingerlike projections, called microvilli, spaced about 0.1 µm apart. The use of the collar as a fi lter is one form of suspension feeding.

Sponges nonselectively consume food particles (bits of detritus, planktonic organisms and bacteria) sized between 0.1 µm and 50 µm. The smallest particles, accounting for about 80% of the particulate organic carbon, are taken into choanocytes by phagocytosis. Choanocytes may acquire protein molecules by pinocytosis. Two other cell types, pinacocytes and archaeocyte play a role in sponge feeding. Sponges may also absorb dissolved nutrients from the water.

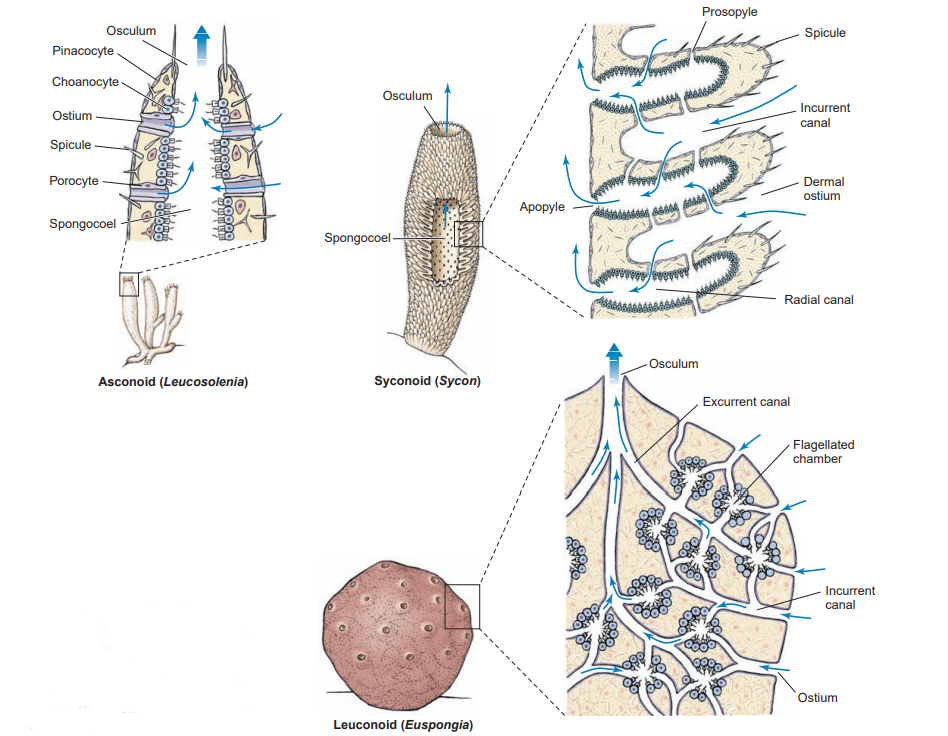

The capture of food depends on the movement of water through the body. There are three main designs for the sponge body differing in the placement of the choanocytes. In the simplest asconoid system, the choanocytes lie in a large chamber called the spongocoel; in the syconoid system, the choanocytes lie in canals; and, in the leuconoid system, the choanocytes lie in distinct chambers. These three designs demonstrate an increase in complexity and efficiency of the water-pumping system, but they do not imply an evolutionary sequence. The leuconoid grade of construction is of clear adaptive value; it has the highest proportion of flagellated surface area for a given volume of cell tissue, so it efficiently meets food demands. This leuconoid grade has evolved independently many times in sponges.

Useful External Links