Epipelagic Fishes

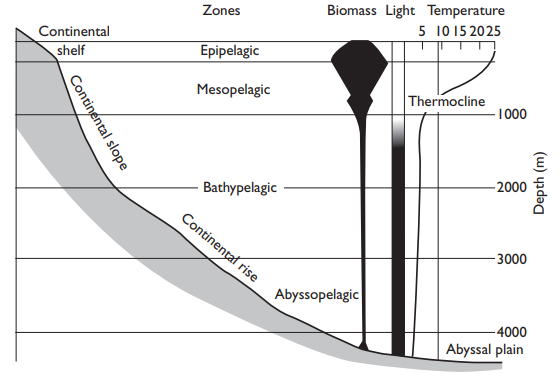

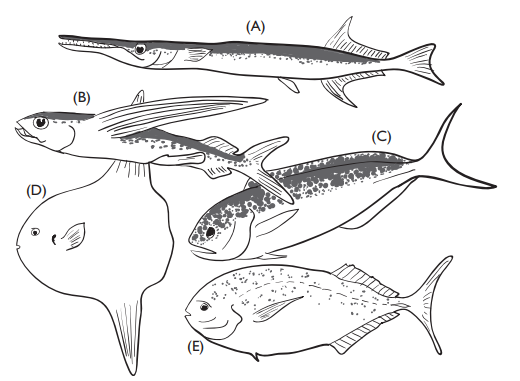

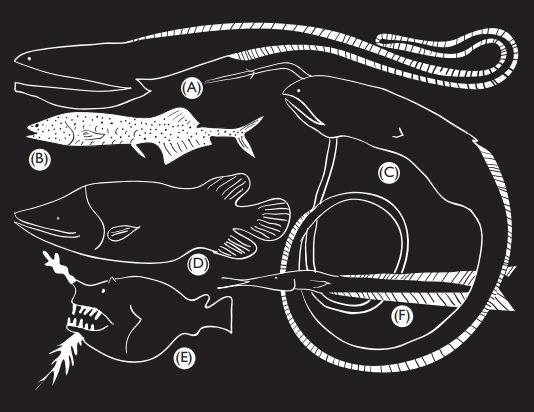

The open ocean beyond the continental shelf covers nearly two-thirds of the surface of the Earth, and some 2500 species are found there, distributed vertically from the uppermost waters to the greatest depths, about half being benthic, half pelagic. Near the surface is the euphotic zone, where light drives (phytoplankton) photosynthesis year-round in the tropics and sub-tropics, and for the warmer part of the year in cold and temperate waters. This zone of primary production (down to 200 m in the clearest waters), supports an epipelagic fish fauna of some 250 species, as well as many larvae of fish from deeper levels. Sharks, flying fish, scombroids such as tunas and billfish, halfbeaks, garfish, the large sunfish Mola, and stromateoids are typical of this zone, and are usually countershaded, colored dark blue above and lighter below so that they match their background when viewed from any angle. Countershading, is found in fishes in almost every habitat, but it is most strongly developed in the epipelagic zone where there is little else to hide a fish from predators.

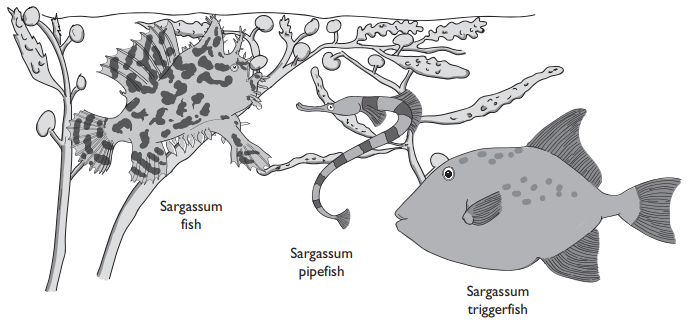

Floating objects attract both smaller epipelagic fishes such as the stromateoid driftfish (Nomeus) and medusafish (Schedophilus), which hide under medusae for protection, as well as larger scombroids preying on the smaller fishes. Since medusae are found at many levels of the ocean it should come as no surprise that even deep-water medusae have their commensal fish associates (Drazen and Robison, 2004), although, in the case of Stygiomedusa gigantea, the fish most likely will be a deep-water species such as the Merlangius merlangus or the ophidiform, Thalassobathia pelagica. The distinctive Sargassum community consists of a variety of fishes and invertebrates that associates with the pelagic brown alga Sargassum. Some, like the Sargassum fish (Histrio histrio) are found nowhere else, and have their closest living relatives among the benthic community, but others associate as juveniles with the seaweed, presumably for protection or food. The perciform wreckfish (Polyprion) is named from its habit of living under floating wreckage, old teacases seemingly being favorite lairs. The epipelagic fauna is richest in warmer regions, but some species, such as the “warm” isurid sharks and blue-fin tuna Thunnus thynnus migrate to colder waters in the productive season.

Mesopelagic Fishes

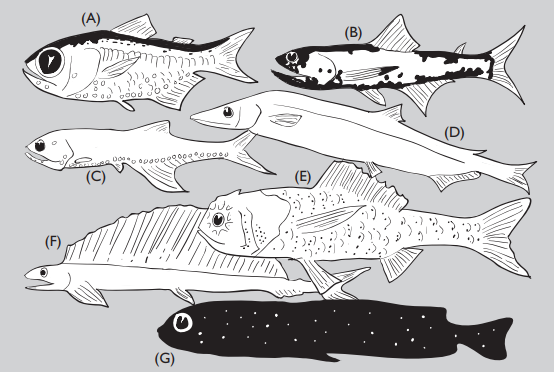

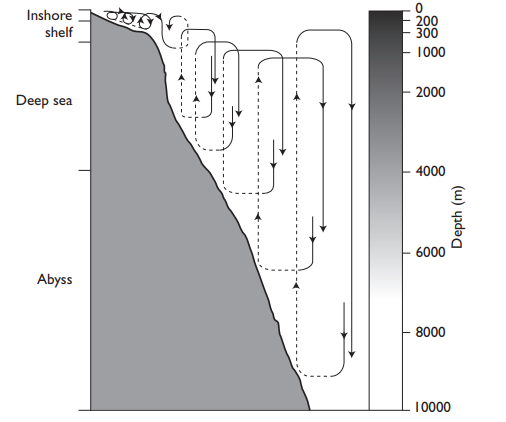

The 900 or so mesopelagic fish species live above the thermocline in a zone where daylight still penetrates; many migrate upwards at night toward the surface, sinking again before dawn, following the migrations of their zooplankton food. Myctophids and several stomiatoids, feeding on copepods and small crustaceans, undertake vertical migrations of 400 m or so up and down each night. Not all vertical migrators travel upward far enough to reach the surface, and differences in the amplitude and timing of such migrations, described as a “ladder of migrations” by Vinogradov (1962), effectively partition different feeding levels, so reducing competition. For example, in the Rockall trough in the northeastern Atlantic, west of the UK, as judged by the species composition of the copepods they feed on, the hatchet fish Argyropelecus olfersi feeds at lower depth horizons than A. hemigymnus, while the third common sternoptychid, Maurolicus muelleri, feeds closest to the surface.

The very rare accidental capture of a large mesopelagic fish such as the megamouth shark (Megachiasma pelagios) shows us that there are some large fishes in this zone. All biologists who have fished in the open ocean with midwater trawls are well aware that these devices never catch the large squid which are known to be abundant (from the stomach contents of marine mammals, much more efficient sampling engines), and so it is possible that other large mesopelagic fish remain to be discovered. Those we can catch are almost all smaller than 30 cm, the myctophid lantern fishes (ca. 250 species) mostly being 10 cm or smaller. Larger fishes, such as the alepisauroids (lancet fishes) up to 2 m long, and chiasmodonts (giant swallowers) with larger jaws and distensible gut and body walls, which feed on fishes and other larger prey, are non-migrators. Many mesopelagic fishes have relatively large eyes and are covered with silvery scales and light organs often arranged in patterns for intraspecific communication or in a form of countershading for camouflage, although others, chiefly predators such as the alepocephalids, are dark brown, black, or red (which, because of the absorption of virtually all red wavelengths by this depth, appears black).

Bathypelagic Fishes

Compared to the more robust mesopelagic fishes, bathypelagic fishes are “economy” designs, reducing the calcification of their skeletons except for the all-important jaws, and with watery muscles. The water content of such fish is high, for example 95% in the angler fish (Melanocetus) and 94% in the gulper eel (Eurypharynx). Even without gas-filled swimbladders, they are near neutral buoyancy. Their hearts are very small, they have very little red muscle, and their low hematocrits (packed red blood-cell volumes, a measure of the blood’s oxygen-carrying capacity) average 8%, compared with the mackerel with a hematocrit of about 50%. Most of the 150 or so species of bathypelagic fishes are ceratioid angler fishes (about 100 species), but the dominant forms in numbers of individuals are black species of the stomiatoid genus Cyclothone. Like angler fishes, Cyclothone species have smaller males than females. As several species of this genus have been shown to be protandrous hermaphrodites, the smaller males eventually transform into larger females and so they are not so much reduced, and do not fuse with the females as do ceratioid males. Many bathypelagic fishes must live a rather sedentary life, hanging in the water waiting opportunistically for the occasional meal to come within range of the jaws. Cyclothone species live on a diet of copepods and small fish, as do angler fishes, some of which (like Melanocetus) can swallow fish two to three times their own length, attracting them within range of the jaws with luminous lures. Although no daylight penetrates to the deep sea, many bathypelagic fishes have normal-sized eyes often with specializations to increase their sensitivity, and the fitful flashes and glows of bioluminescence must obviously be significant in their lives.

Benthopelagic Fishes

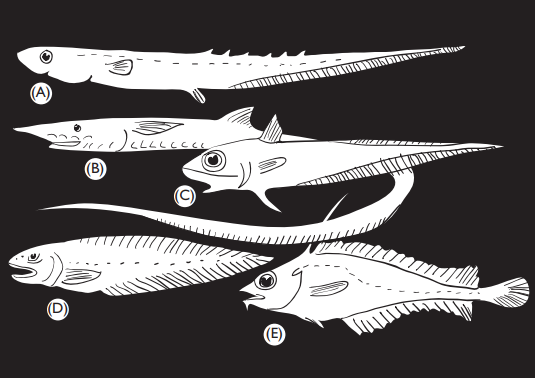

Rather surprisingly, the great majority of bottom-living fishes from upper slope levels at 200 m or so to around 8000 m in the deep ocean are neutrally buoyant and live not on the bottom but just off it, like the deep-sea squaloid sharks (floating by means of their large oil-filled livers). Although shallow-water rays are dense fish and rest on the bottom, their deep sea relatives resemble the squaloids in having very large livers and are also close to neutral buoyancy, presumably also being benthopelagic. Recent analysis of a global data set shows a trend of rapid disappearance of elasmobranch species with depth when compared with bony fishes (Priede et al., 2005). Sharks, apparently well adapted to life at high pressures, are conspicuous on slopes down to 2000 m including scavenging at food falls such as dead whales. It has been suggested that they are excluded from the abyss by their high energy demands created by the necessity for near-constant swimming and an oil-rich liver for buoyancy, which cannot be sustained in extreme oligotrophic conditions as are found away from the slope environment.

Among the teleosts, cusk-eels (ophidioids) and rat-tails (macrourids) dominate this cosmopolitan fauna, whose biomass may be considerable, and, like the deep-sea cods (morids), deep-sea eels, notacanths, and halosaurs, all have gas-filled swimbladders. They feed on other fishes, benthopelagic zooplankton, and benthic invertebrates. Apart from those around thermal vents, the benthopelagic and benthic invertebrates ultimately depend on organic matter such as fecal material raining down from surface waters, and it is understandable that the biomass of the plankton decreases rapidly with depth. For example, at 1000 m it is only 1% of that at the surface, and at 5000 m only about 0.01%.

Around thermal vents and metthane seeps, however, food for benthopelagic fishes is richer, symbiotic bacteria supplying the energy source for worms, crustaceans, and molluscs.

Benthic Fishes

In contrast to the benthopelagic fishes, benthic fishes lack swim bladders and are dense, resting on the bottom, sometimes, like tripod fishes (Bathypterois spp.) on stiff elongate fin-rays, sitting aligned into the currents that bring zooplankton to their mouths. Tripod-fish and green-eyes (both chloropthalmids) and lizard-fishes (synodontids) are the dominant forms, and in temperate and polar waters, eel-pouts (zoarcids), and seasnails (liparids) are also important. As with the benthopelagic fishes, benthic fishes of these kinds often show interesting specialization of the eyes, and some, such as Chloropthalmus, have luminous organs.

Because of the lack of cues such as light and temperature change, it was once thought that there was no seasonality in the deep sea. This is not so – the fall-out of detritus depends on seasonal production cycles at the surface and, certainly in higher latitudes, there are annual growth cycles in deep-sea fish species.