The oxygen acquired (from water or air), and the carbon dioxide excreted at the gills, have to be transported around the body by the circulation of the blood. In fishes using the gills as a gas exchanger, the primary circulation is single, blood leaves the heart to pass first through the gill capillary bed, thence to the systemic capillaries, and back to the heart. Usually the gills account for approximately 30% of the total resistance to blood flow, the remainder being in the visceral and somatic vasculature, but in tunas, which have high oxygen requirements and large gill areas, the gills account for up to 57% of the total resistance.

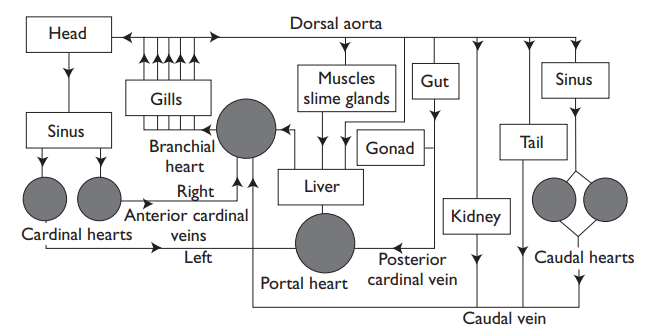

In most fishes, blood pressures in the primary circulation are rela-tively low (very low in hagfishes), although once again tunas are the exception, and pressures in the ventral aorta in resting tunas reach 87 mmHg (10.58 kPa), and in exercising fish 90 mmHg (12.4 kPa). In the venous system, pressures are very low, and may even be sub-ambient; venous return is assisted by an unusual variety of pumps including accessory hearts. Hagfishes, for example, have no fewer than five “hearts” in addition to the usual one.

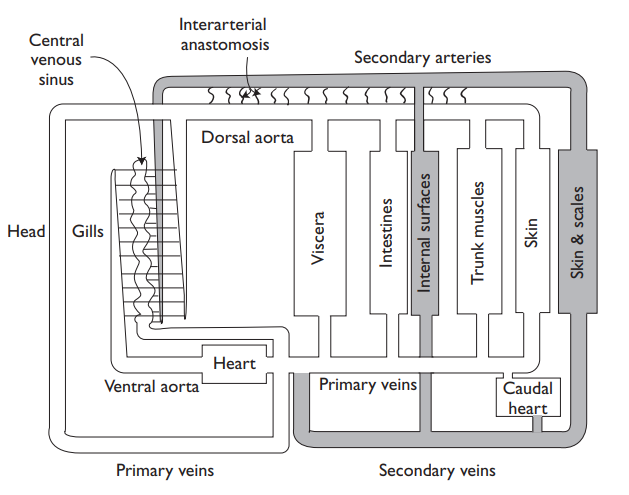

As well as the primary circulation, many kinds of fish, such as lampreys, elasmobranchs, and euteleosts, have an unusual secondary circulation, connected to the primary circulation by fine-bore coiled arterio-arterial anastamoses. These were first discovered in 1929, but not until Vogel and Claviez (1981) examined corrosion casts by scanning microscopy (which gave superb pictures of minute vessels and their connections) was it accepted that these were not lymphatics (so regarded even in some recent texts), but a separate secondary circulation.

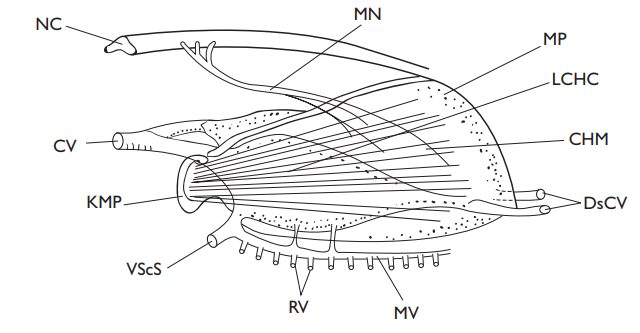

After receiving blood from the primary circu-lation via small arterioles whose connections are guarded by fingers from endothelial cells, the vessels of the secondary circulation form their own cap-illary beds in the fins, gills, mouth, skin, and peritoneum, then forming secondary vessels which join the primary circulation at caudal and cutaneous veins. While not easy to make unambiguous measurements, it seems that the serum in the secondary circulation is similar to that in the pri-mary circulation, although hematocrit levels are much lower, and while vol-ume is much larger (perhaps 1.5 times that of the primary circulation), flow rates are much lower.

So there are two rather different parallel circulations in fish, what might be the function of the secondary? One possibility is that because the secondary circulation capillaries seem directed to exposed epithelia near the ambient water, they may function in controlling volume, ion levels, or in immunoregu-lation. But more experiments are needed, and, although it is tempting to guess a nutritive function, it is probably more sensible to await more data. Only in lungfish is there a lymphatic system and the secondary circulation is absent.

In general, the teleost circulatory system is more efficient than that of elas-mobranchs, blood volume is lower, as is cardiac output, and narrower veins occur instead of venous sinuses. There are interesting exceptions to some of these generalizations, which will be considered later, for example, in the Antarctic icefish (Chaenocephalus aceratus), which lacks hemoglobin, Q is exceptionally high.