Apart from the special case of the channichthyid icefishes, most oxygen in the blood is carried by red cell hemoglobin, oxygenated when Po2 is high and deoxygenated when it falls, according to the oxygen dissociation curve (blood Po2 plotted against the amount of O2 bound to the hemoglobin). Oxygen dissociation curves are always non-linear, and in active fishes, usually sigmoid, this shape representing a compromise between high O2 affinity needed for loading at the gills and lower affinity for unloading at the tissues. The normal working range in the fish usually lies on the steep part of the curve so that much O2 can be unloaded for small changes in Po2.

The slope of the dissociation curve can be changed by changes in pH; with increase in acidity, the curve is usually shifted markedly to the right. This is the Bohr shift (defined as the shift or change in log 50% O2 saturation divided by the pH change causing it. It results from pH dependent configurational changes in the hemoglobin molecules which inhibit O2 binding; what it means in practice is that O2 is unloaded at sites where Pco2 is high, just where it is needed by the fish. In many fishes, increase in Pco2 not only shifts the dissociation curve to the right, but it also prevents complete oxygenation of the hemoglobin, thus depressing the curve.

The lowering of blood O2-carrying capacity (rather than O2 affinity) in this way is the Root shift (the Root shift is used by the fish to drive O2 into the swimbladder from the rete). The Root shift is really a very extreme case of the Bohr shift, and it is found in the blood of fishes with swimbladders or other O2-concentrating retia (like those of the choroid plexus of the eye) but is absent from elasmobranchs that do not possess such retia. Air-breathing fishes such as lungfish or the electric eel (Electrophorus) have hemoglobins that are rather insensitive to Pco2, and they need to have this reduced Bohr shift, because Pco2 at the gas exchanger and in the blood will be higher than in water-breathing fishes.

Hagfishes and lampreys have monomeric hemoglobins, but in all other fishes the hemoglobins are tetrameric (as they are in mammals), and polymorphic. Several different hemoglobins may occur in one fish, perhaps to adapt the gas-transport system to changing conditions, as in the American eel (Anguilla rostrata), where one type has a high O2 affinity in seawater, the other in freshwater. A large Root effect is seen in fish living in oxygen-rich water, a small effect in oxygen-poor water.

CO2 Transport

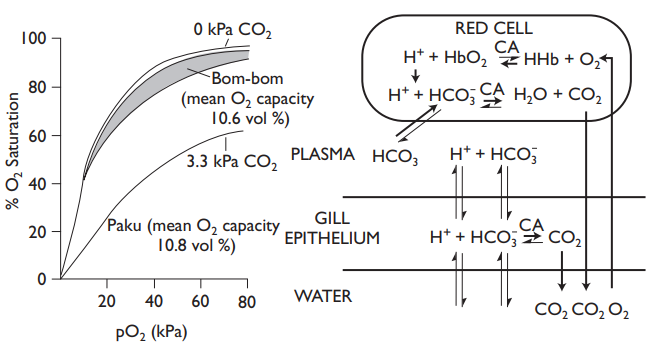

Only a small proportion of the CO2 diffusing into the blood at the tissues remains dissolved in the plasma; most is hydrated to the bicarbonate ion (about 95% of CO2 in the venous blood is plasma HCO3–), and so CO2 from the tissues is transported in the blood mainly as HCO3s–. Rehydration of CO2 to HCO3– is slow in the veins, taking place after the venous blood has left the respiring tissue, but is rapidly catalyzed by carbonic anhydrase in the red cells, where O2 is driven off the hemoglobin in the respiring tissues as it binds the resulting protons.

HCO3– entry in the red cells is accompanied by water entry (to rehydrate the HCO3–) and by Cl– (to maintain electro-neutrality). This chloride shift increases the osmolarity of the red cells, which therefore swell slightly so that their volume becomes 2–3% greater in venous than in arterial blood. At the gills total blood CO2 is reduced by 10–20%, mainly because HCO3– falls by 20% in the plasma. One scheme by which this could occur is shown in the lower half , where carbonic anhydrasecatalyzed CO2 produced in the red cell from HCO3– diffuses away across the plasma and gill epithelium to the water flowing over the gills. Carbonic anhydrase is present in the gill epithelium, but does not appear to play a role in CO2 excretion.

Oxygen and carbon dioxide transport are complementary, and combine to make a system efficient enough to satisfy the gas transport demands of such active fishes as tunas. Probably it is generally true that fishes use most oxygen in the red muscle, driving cruising swimming, and in the fast-swimming scombroids this tissue is extremely well vascularized. Capillary fiber ratios up to 4.5:1 and external diffusion distances of around 10mm are seen in skipjack (Katsuwonus) red muscle and compare very favorably with those of mammalian muscle.