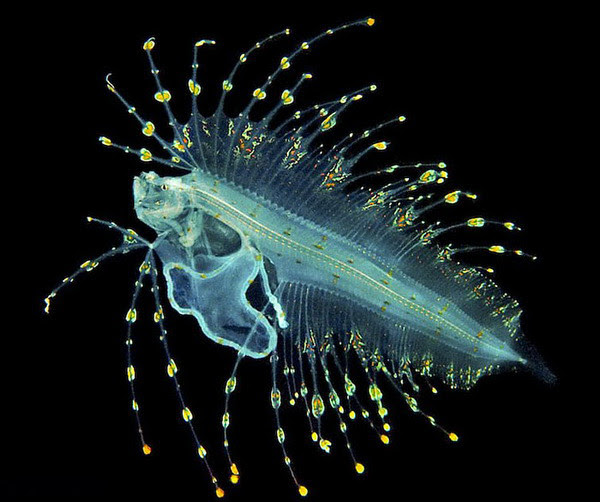

Rotifera (ro-tif -e-ra) (L. rota, wheel, fera, those that bear) derivet heir name from the characteristic ciliated crown, or corona, that, when beating, often gives the impression of rotating wheels . Rotifers range from 40 µ m to 3 mm in length, but most are between 100 and 500 µ m long. There are about 2000s pecies of rotifers.

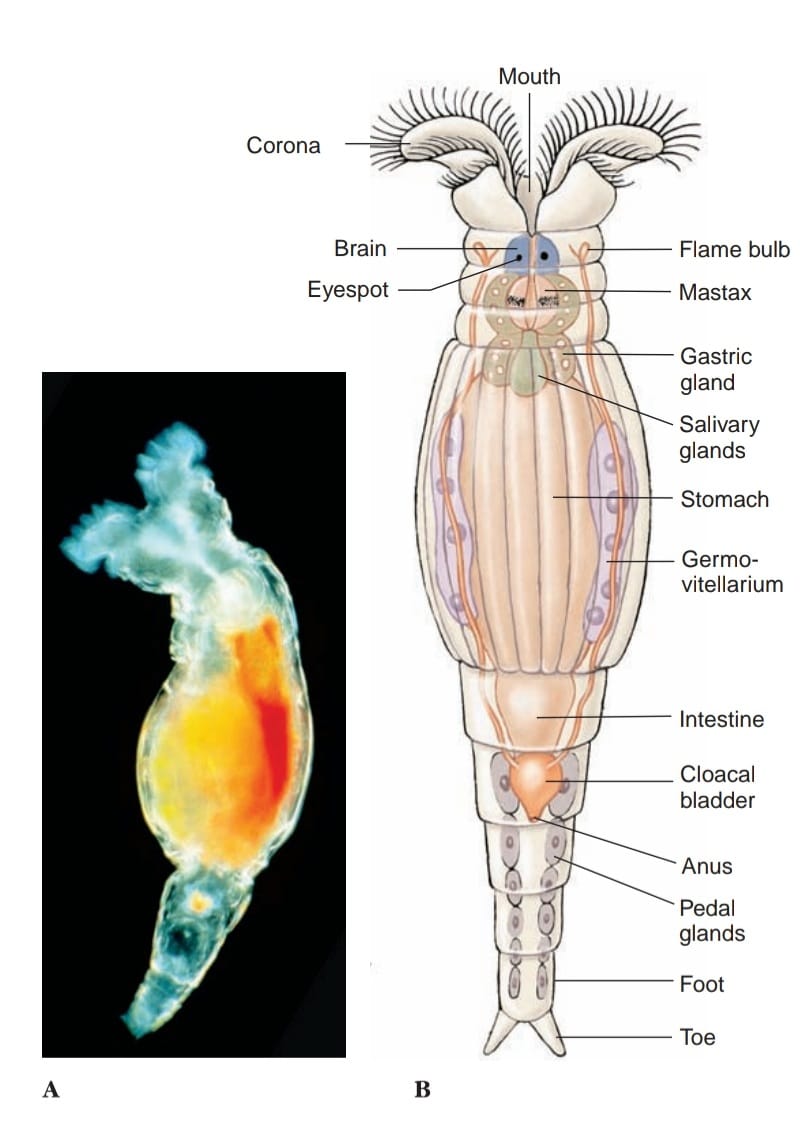

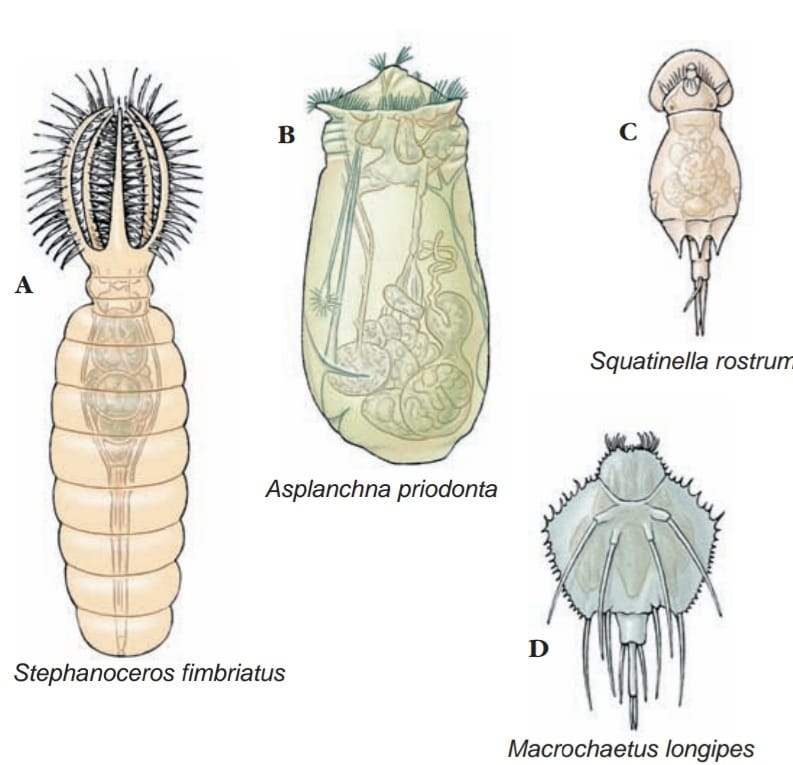

Rotifers are adapted to many ecological conditions. Most species are benthic, living on the bottom or in vegetation of ponds or along the shores of freshwater lakes where they swim or crawl on the vegetation. Some species live in the water film between sand grains of beaches (meiofauna). Pelagic forms are common in surface waters of freshwater lakes and ponds. Some rotifers are epizoic (live on the body of another animal) or parasitic. Some rotifers have bizarre shapes . Their shapes are often correlated with their mode of life. Floaters are usually globular and saclike; creepers and swimmers are somewhat elongated and wormlike; and sessile types are commonly vaselike, with a thickened outer epidermis (lorica). Some are colonial.

Many species of rotifers can endure long periods of desiccation, during which they resemble grains of sand. Desiccated rotifers are very tolerant of environmental extremes. For example, some moss-dwelling species have been dried for up to 4 years beforer eviving upon addition of water. Other rotifers have survived temperatures as cold as 272 C before being successfully revived.

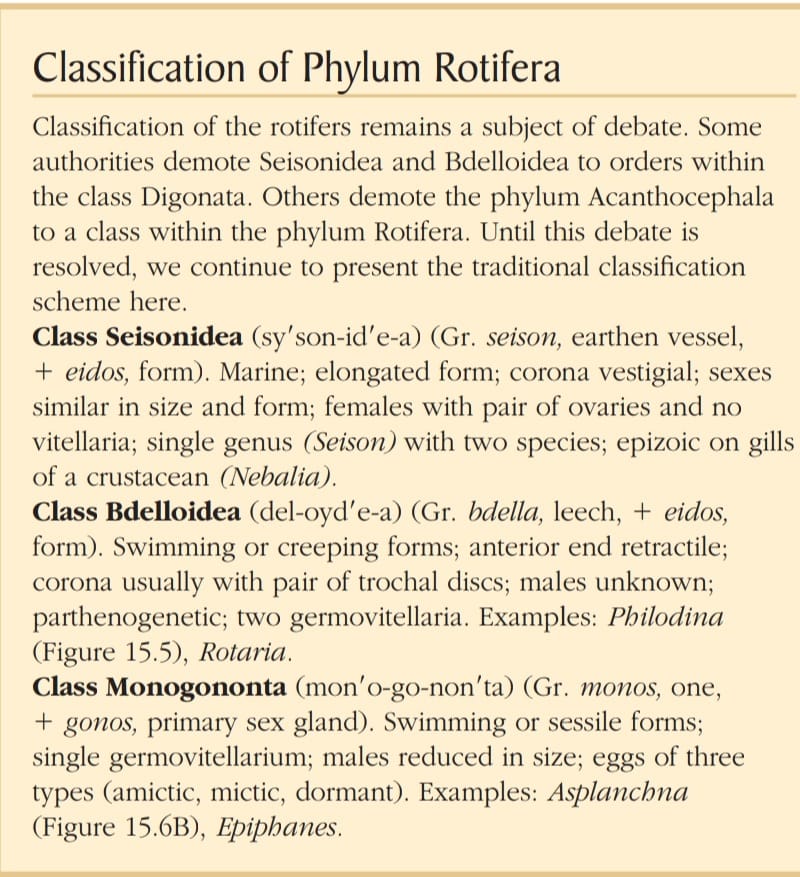

A rotifer’s body comprises a head bearing a ciliated corona, a trunk, and a posterior tail, or foot. Except for the corona, the body is nonciliated and covered with a cuticle. One of the best-known genera is Philodina (Gr. philos, fond of, dinos, whirling) Their ciliated corona, or crown, surrounds a nonciliated central area of their head, which may bear sensory bristles or papillae. A head’s appearance depends on which of several types of corona it has—usually a circlet of some sort, or a pair of trochal (coronal) discs (the term trochal comes from a Greek word meaning wheel). Cilia on the corona beat in succession, giving the appearance of a revolving wheel or pair of wheels. Their mouth is located in the corona on the midventral side. Coronal cilia function in both locomotion and feeding.

The trunk may be elongated, as in Philodina , or saccular in shape . The trunk contains visceral organs and often bears sensory antennae. The body wall of many species is superficially ringed to simulate segmentation. Although some rotifers have a true, secreted cuticle, all have a fibrous layer within their epidermis. The fibrous layer in some is quite thick and forms a caselike lorica, which is often arranged in plates or rings.

Their foot is narrower and usually bears one to four toes. The cuticle of the foot may be ringed so that it is telescopically retractile. The foot is an attachment organ and contains pedal glands that secrete an adhesive material used by both sessile and creeping forms. It is tapered gradually in some forms and sharply set off in others . In swimming pelagic forms, the foot is usually reduced. Rotifers can move by creeping with leechlike movements aided by the foot, or by swimming with the coronal cilia, or both.

Underneath the cuticle is a syncytial epidermis, which secretes the cuticle, and bands of subepidermal muscles, some circular, some longitudinal, and some running through the pseudocoel to visceral organs. The pseudocoel is large, occupying the space between body wall and viscera. It is filled with fluid, some of the muscle bands, and a network of mesenchymal ameboid cells.

The digestive system is complete. Some rotifers feed by sweeping minute organic particles or algae toward the mouth by beating the coronal cilia. Cilia dispose of larger unsuitable particles. Their pharynx (mastax) is fitted with a muscular portion equipped with hard jaws (trophi) for sucking in and grinding food particles. The (mastax) can be a crushing and grinding form among suspension feeders or a grasping and piercing form in predatory species.

The constantly chewing mastax is often a distinguishing feature of these tiny animals. Carnivorous species feed on protozoa and small metazoans, which they capture by trapping or grasping. Trappers have a funnel-shaped area around the mouth. When small prey swim into the funnel, the lobes fold inward to capture and to hold them until they are drawn into the mouth and pharynx. Hunters have trophi that are projected and used like forceps to seize prey, bring it back into the pharynx, and then pierce it or break it so that edible parts may be recovered and the rest discarded. Salivary and gastric glands are believed to secrete enzymes for extracellular digestion. Absorption occurs in the stomach.

The excretory system typically consists of a pair of protonephridial tubules, each with several flame cells, that empty into a common bladder. The bladder, by pulsating, empties into a cloaca—into which the intestine and oviducts also empty. The fairly rapid pulsation of the protonephridia—one to four times per minute—would indicate that protonephridia are important osmoregulatory organs. Water apparently enters through the mouth rather than across the epidermis; even marine species empty their bladder at frequent intervals.

The nervous system contains a bilobed brain, dorsal to the mastax in the “neck” region of the body, which sends paired nerves to the sense organs, mastax, muscles, and viscera. Sensory organs include paired eyespots (in some species such as Philodina), sensory bristles and papillae, and ciliated pits and dorsal antennae.

Useful External Links

- Rotifers: Structure, Characteristics, and Classification by Brandon Ward

- Annotated checklist of the rotifers (Phylum Rotifera), with notes on nomenclature, taxonomy and distribution by Hendrik H. Segers

- Global diversity of rotifers (Rotifera) in freshwater by Hendrik Segers