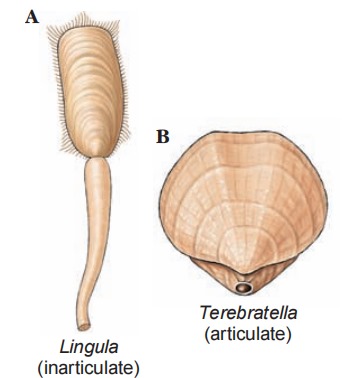

Brachiopoda (brak-i-op’ – o-da) (Gr. brachio¯n, arm, pous, podos, foot), or lamp shells, are an ancient group. Although about 325 species are now living, some 12,000 fossil species, which once flourished in Paleozoic and Mesozoic seas, have been described. Modern forms have changed little from early ones. Genus Lingula (L. tongue) is considered a “living fossil,” having existed virtually unchanged since Ordovician times. Most modern brachiopod shells range between 5 and 80 mm in length, but some fossil forms reached 30 cm.

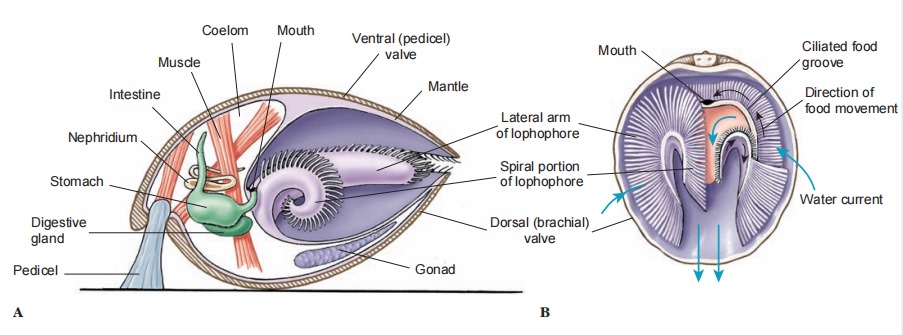

Brachiopods are attached, bottom-dwelling, marine forms that mostly prefer shallow water, although they are known from nearly all ocean depths. Externally brachiopods resemble bivalved molluscs in having two calcareous shell valves secreted by a mantle. They were, in fact, classified with molluscs until the middle of the nineteenth century, and their name refers to the arms of the lophophore, which were thought homologous to the mollusc foot. Brachiopods, however, have dorsal and ventral valves instead of right and left lateral valves as do bivalve molluscs and, unlike bivalves, most of them are attached to a substrate either directly or by means of a fleshy stalk called a pedicel. Some, such as Lingula, live in vertical burrows in sand or mud. Muscles open and close the valves and provide movement for the stalk and tentacles.

In most brachiopods the ventral (pedicel) valve is slightly larger than the dorsal (brachial) valve, and one end projects in the form of a short, pointed beak perforated where the fleshy stalk passes through the shell to attach to the substratum . In many the pedicel valve is shaped like a classic oil lamp of ancient Greece and Rome, so that brachiopods came to be called “lamp shells.”

Shell structure distinguishes the two classes of branchiopods. Shell valves of Articulata have a connecting hinge with an interlocking tooth-and-socket arrangement, as in Terebratella (L. terebratus, a boring, ella, dim. suffix); those of Inarticulata lack the hinge and are held together by muscles only, as in Lingula and Glottidia (Gr. glottidos, mouth of windpipe).

Their body occupies only the posterior part of the space between the valves , and extensions of the body wall form mantle lobes that line and secrete the shell. Their large horseshoe-shaped lophophore in the anterior mantle cavity bears long, ciliated tentacles used in respiration and feeding. Ciliary water currents carry food particles between the gaping valves and over the lophophore. Tentacles catch food particles, and ciliated grooves carry the particles along the arm of the lophophore to their mouth. Rejection tracts carry unwanted particles to the mantle lobe where they are swept out in ciliary currents. Organic detritus and some algae are apparently primary food sources. A brachiopod’s lophophore not only creates food currents, as do other lophophorates, but also seems to absorb dissolved nutrients directly from environmental seawater.

As in other lophophorates, the posterior metacoel bears the viscera. One or two pairs of nephridia open into the coelom and empty into the mantle cavity. Coelomocytes, which ingest particulate wastes, are expelled by nephridia. There is an open circulatory system with a contractile heart. Lophophore and mantle are probably the chief sites of gaseous exchange. There is a nerve ring with a small dorsal and a larger ventral ganglion. Most species have separate sexes, and temporary gonads discharge gametes through the nephridia. Most fertilization is external, but a few species brood their eggs and young.

Cleavage is radial, and coelom and mesoderm formation in at least some brachiopods is enterocoelic. The blastopore closes, but its relationship to the mouth is uncertain. In articulates, meta morphosis of larvae occurs after they have attached by a pedicel. In inarticulates, juveniles resemble a minute brachiopod with a coiled pedicel in the mantle cavity. There is no metamorphosis. As a larva settles, its pedicel attaches to the substratum, and adult existence begins.

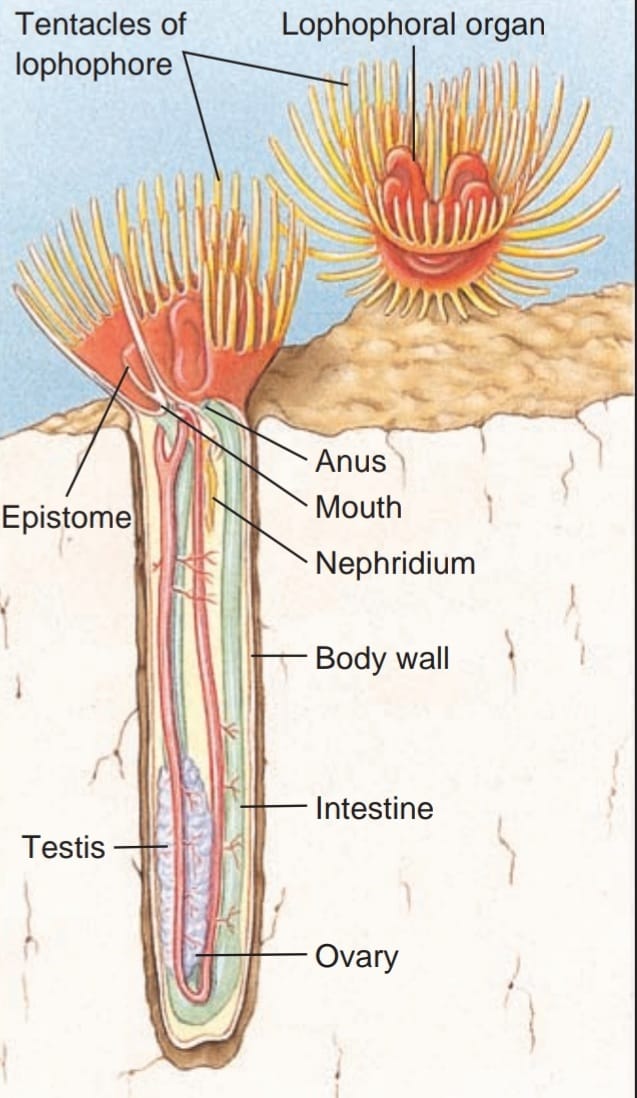

Phylum Phoronida (fo-ron’ – i-da) (L. Phoronis, in mythology, surname of Io, who was turned into a white heifer) contains approximately 20 species of small, wormlike animals. Most live on the substrate below shallow coastal waters, especially in temperate seas. They range from a few millimeters to 30 cm in length. Each worm secretes a leathery or chitinous tube in which it lies free, but which it never leaves. The tubes may be anchored singly or in a tangled mass on rocks, shells, or pilings or buried in sand. They thrust out the tentacles on the lophophore for feeding, but a disturbed animal can withdraw completely into its tube.

A lophophore has two parallel ridges curved in a horseshoe shape, the bend located ventrally and the mouth lying between the two ridges . Horns of the ridges often coil into twin spirals. Each ridge carries hollow ciliated tentacles, which, like the ridges themselves, are extensions of the body wall.

section.

Cilia on the tentacles direct a water current toward a groove between the two ridges, which leads toward the mouth. Plankton and detritus caught in this current become entangled in mucus and are carried by cilia to the mouth. The anus lies dorsal to the mouth, outside the lophophore, flanked on each side by a nephridiopore. Water leaving the lophophore passes over the anus and nephridiopores, carrying away wastes. Cilia in the stomach area of the U-shaped gut aid food movement.

The body wall consists of cuticle, epidermis, and both longi tudinal and circular muscles. The protocoel is present as a small cavity in the epistome; it connects to the mesocoel along the lateral aspects of the epistome . A septum separates the metacoel from the mesocoel. Phoronids have an extensive system of contractile blood vessels in a functionally but not technically closed circulatory system. They have no heart. Their blood contains hemoglobin within nucleated cells. There is a pair of metanephridia. A nerve ring sends nerves to tentacles and body wall, but the system is diffuse and lacks a distinct ganglion that could be called a brain. A single giant motor fiber lies in the epidermis, and an epidermal nerve plexus supplies the body wall and epidermis.

There are both monoecious (the majority) and dioecious species of Phoronida, and at least two species reproduce asexually. Fertilization may be internal or external, but contrary to early reports cleavage is radial. Coelom formation is by a highly modified enterocoelous route, but the blastopore becomes the mouth. A free-swimming, ciliated larva, called an actinotroch, which sinks to the bottom, metamorphoses into an adult, secretes a tube, and becomes sessile.

Useful External Links