Feeding habits of gastropods are as varied as their shapes and habitats, but all include use of some adaptation of the radula. Most gastropods are herbivorous, rasping particles of algae from hard surfaces. Some herbivores are grazers, some are browsers, and some are planktonic feeders. Haliotis, the abalone, holds seaweed with its foot and breaks off pieces with its radula. Land snails forage at night for green vegetation.

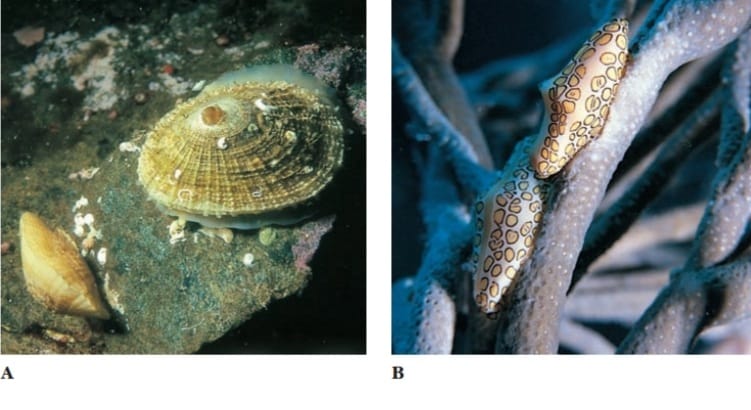

Some snails, such as Bullia and Buccinum, are scavengers living on dead and decaying flesh; others are carnivores that tear their prey with radular teeth. Melongena feeds on clams, especially Tagelus, the razor clam, thrusting its proboscis between the gaping shell valves. Fasciolaria and Polinices feed on a variety of molluscs, preferably bivalves. Urosalpinx cinerea, oyster borers, drill holes through the shells of oysters.

Their radula, bearing three longitudinal rows of teeth, is used first to begin the drilling action; then the snails glide forward, evert an accessory boring organ through a pore in the anterior sole of their foot, and hold it against the oyster’s shell, using a chemical agent to soften the shell. Short periods of rasping alternate with long periods of chemical activity until a neat round hole is completed. With its proboscis inserted through the hole, a snail may feed continuously for hours or days, using its radula to tear away the soft flesh. Urosalpinx is attracted to its prey at some distance by sensing some chemical, probably one released in metabolic wastes of the prey.

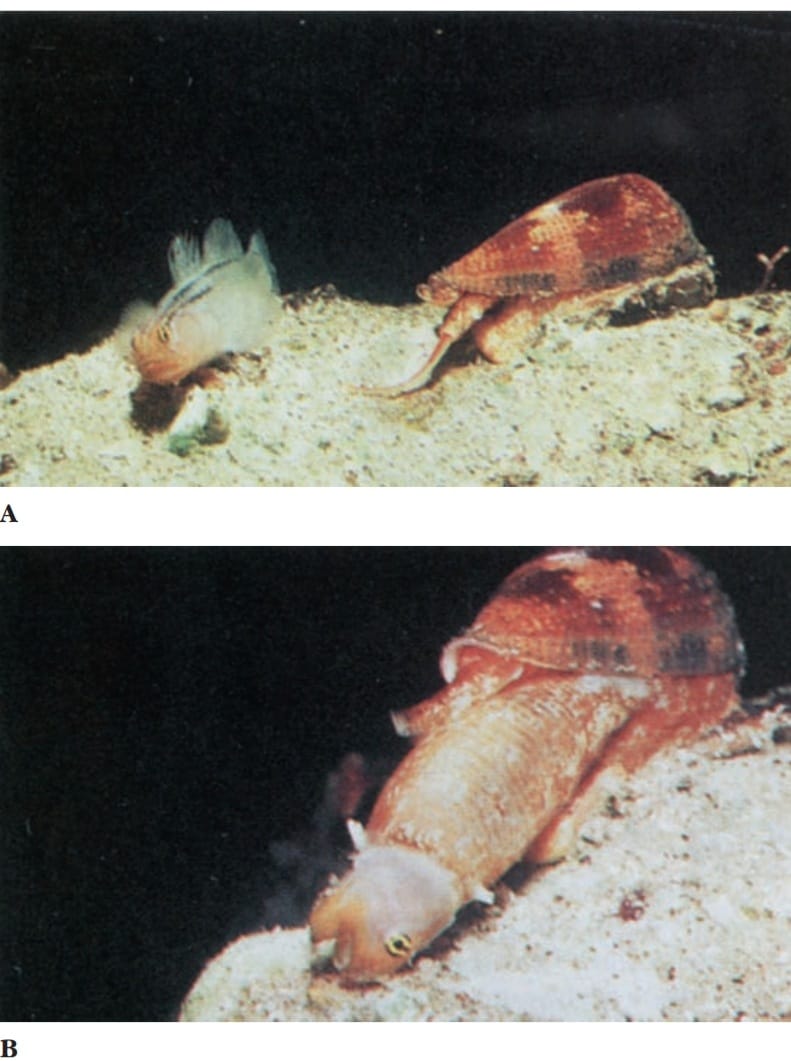

Cyphoma gibbosum and related species live and feed on gorgonians (phylum Cnidaria,) in shallow, tropical coral reefs. These snails are commonly known as flamingo tongues. During normal activity their brightly colored mantle entirely envelops the shell, but it can be quickly withdrawn into the shell aperture when the animal is disturbed. Members of genus Conus feed on fish, worms, and molluscs. Their radula is highly modified for prey capture.

A gland charges the radular teeth with a highly toxic venom. When Conus senses the presence of its prey, a single radular tooth slides into position at the tip of the proboscis. Upon striking the prey, the proboscis expels a tooth like a harpoon, and the venom immediately paralyzes the prey. This is an effective adaptation for a slowly moving predator to prevent escape of a swiftly moving prey.

Some species of Conus can deliver very painful stings, and in several species the sting is lethal to humans. The venom consists of a series of toxic peptides, and each Conus species carries peptides (conotoxins) that are specific for the neuroreceptors of its preferred prey. Conotoxins have become valuable tools in research on the various receptors and ion channels of nerve cells.

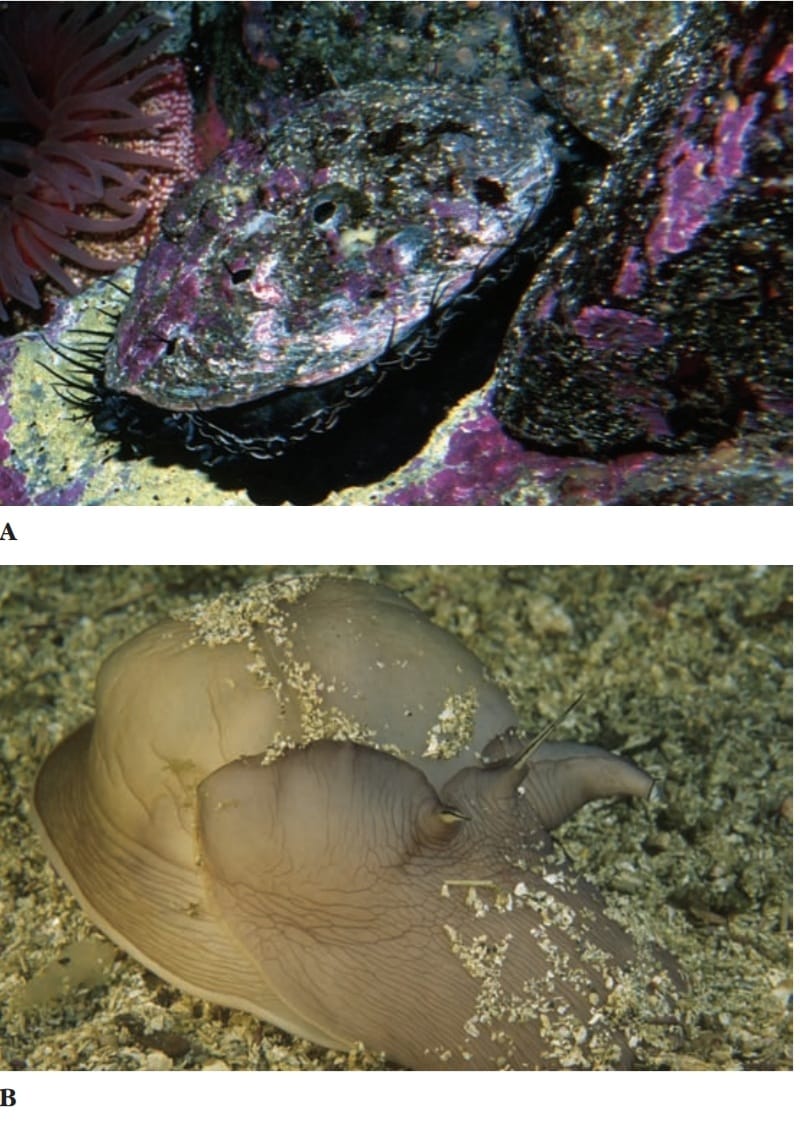

Some gastropods, such as the queen conch ( Strombus gigas ), feed on organic deposits on the sand or mud. Others collect the same sort of organic debris but can digest only microorganisms contained in it. Some sessile gastropods, such as some limpets, are ciliary feeders that use gill cilia to draw in particulate matter, roll it into a mucous ball, and carry it to their mouth. Some sea butterflies secrete a mucous net to catch small planktonic forms; then they draw the web into their mouth.

After maceration by the radula or by some grinding device, such as a gizzard in the sea hare Aplysia, digestion is usually extracellular in the lumen of the stomach or digestive glands. In ciliary feeders the stomachs are sorting regions, and most digestion is intracellular in digestive glands.

Useful External Links