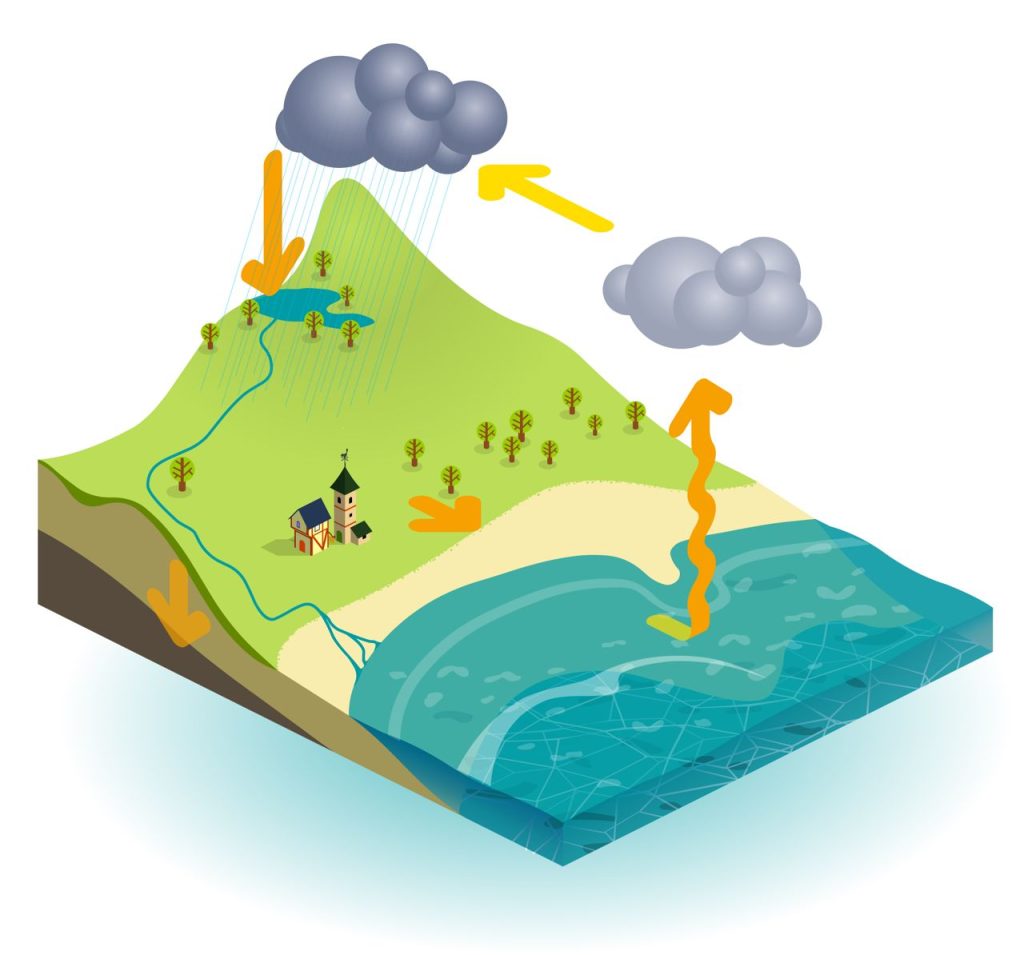

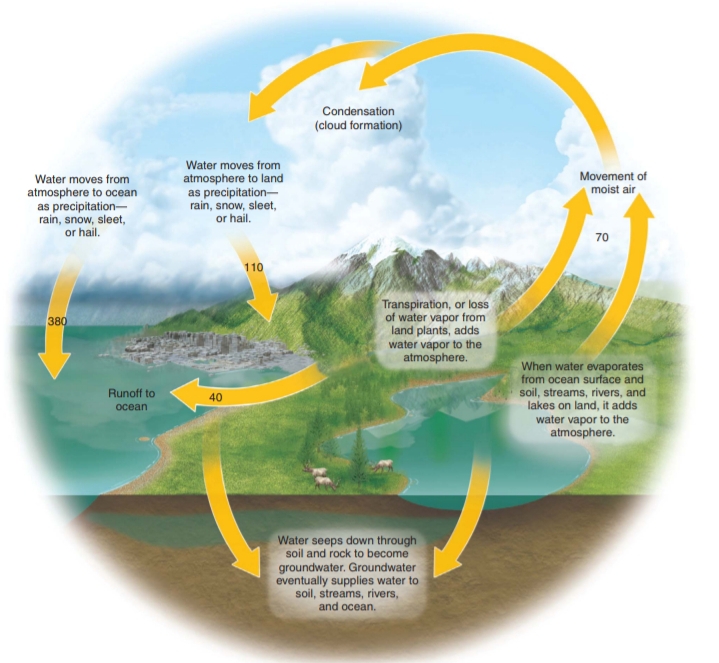

The hydrologic cycle, or water cycle, moves water from land and ocean to the atmosphere. Water from the oceans and land surfaces evaporates, changing state from liquid to vapor and entering the atmosphere.

Total evaporation is about six times greater over oceans than land because oceans cover most of the planet and because land sur-faces are not always wet enough to yield much water.

Water vapor in the atmosphere can condense or depos it to form clouds and precipitation, which falls to Earth as rain, snow, or hail. There is nearly four times more precipitation over oceans than precipitation over land.

When precipitation hits land, it can take three different courses. First, it can evaporate and return to the atmosphere as water vapor. Second, it can sink into the soil and then into the cracks and crevices in rock layers below as groundwater.

As we will see in later chapters, this subsurface water emerges from below to feed rivers, lakes, and even ocean margins. Third, precipitation can run off the land, concentrating in streams and rivers that eventually carry it to the ocean or to lakes. This flow is known as runoff.

Because our planet contains only a fixed amount of water, a global balance must be maintained among flows of water to and from the lands, oceans, and atmosphere. Evaporation leaving the ocean is approximately 420 km 3/yr (101 mi 3/yr), while the amount entering the ocean via precipitation is 380 km 3/yr (91 mi 3/yr).

Clearly, there is an imbalance between the amount of water lost to evaporation and the amount gained through precipitation. This imbalance is made up by the 40 km 3/yr (10 mi 3/yr) that flows from the land back to the ocean.

Similarly, there is a balance for the land surfaces of the world. Of the 110 km 3/yr (27 mi 3/yr) of water that falls on the land surfaces, 70 km 3/yr (17 mi 3/yr) is reevaporated back into the atmosphere. The remaining 40 km 3/yr (10 mi 3/yr) stays in the form of liquid water and eventually flows back into the ocean.

Of all these pathways, we will be most concerned with only one aspect of the hydrologic cycle: the flow of water from the atmosphere to the surface in the form of precipitation. To understand this process, we first need to examine how water vapor in the atmosphere is converted into clouds and, subsequently, into precipitation.

Use External Links