The largest class of annelids is the Polychaeta (Gr. polys, many, chaite¯, long hair) with more than 10,000 species, most of them marine. Although most polychaetes are 5 to 10 cm long, some are less than 1 mm, and others may be as long as 3 m. They may be brightly colored in reds and greens, iridescent, or dull. Many polychaetes are euryhaline and can tolerate a wide range of environmental salinity. The freshwater polychaete fauna is more diversified in warmer regions than in temperate zones.

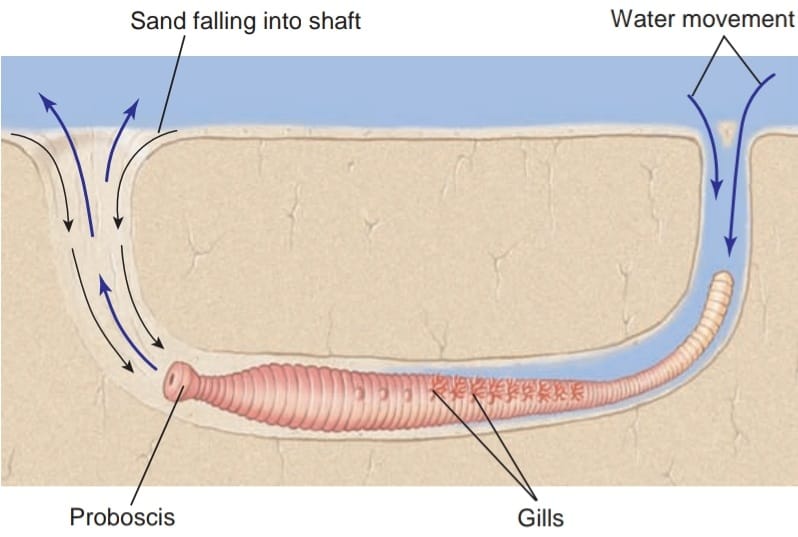

Many polychaetes live under rocks, in coral crevices, or in abandoned shells. A number of species burrow into mud or sand and build their own tubes on submerged objects or in bottom sediment. Others adopt the tubes or homes of other animals, and some are planktonic. They are extremely abundant in some areas; for example, a square meter of mudflat may contain thousands of polychaetes. They play a significant part in marine food chains because they are eaten by fish, crustaceans, hydroids, and many other predators.

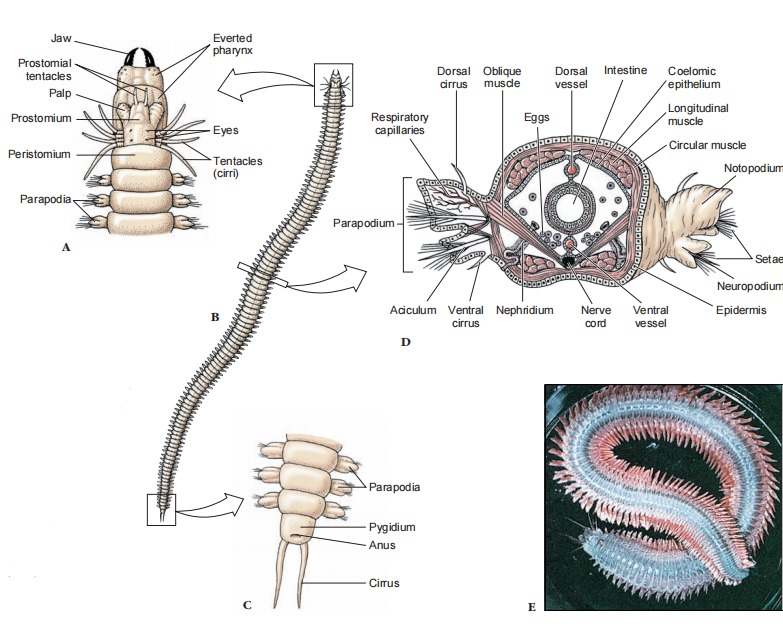

Polychaetes differ from other annelids in having a well differentiated head with specialized sense organs; paired append ages, called parapodia, on most segments; and no clitellum. As their name implies, they have many setae, usually arranged in bundles on the parapodia. They exhibit the most pronounced differentiation of body segments and specialization of sensory organs found in annelids.

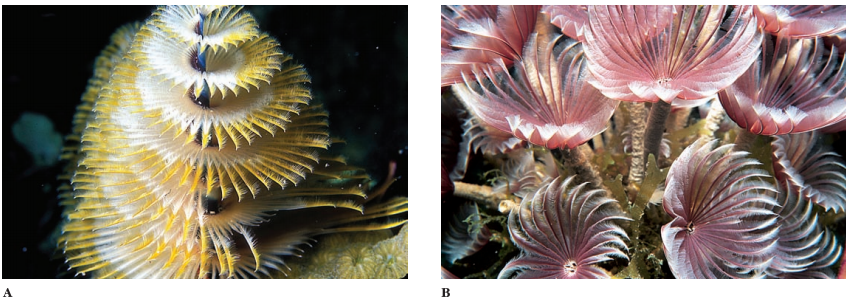

Polychaetes are often divided into two morphological groups based on their activity: sedentary polychaetes and errant (free moving) polychaetes. Sedentary polychaetes spend much or all of their time in tubes or permanent burrows. Many of them, especially those that live in tubes, have elaborate devices for feeding and respiration. Errant polychaetes (L. errare, to wander), include free-swimming pelagic forms, active burrowers, crawlers, and tubeworms that only leave their tubes for feeding or breeding. Most of these, like clam worms in the genus Nereis (Gr. name of a sea nymph), are predatory and equipped with jaws or teeth. They have an eversible, muscular pharynx armed with teeth that can be thrust out with surprising speed to capture prey.

Form and Function

A polychaete typically has a prostomium, which may or may not be retractile and which often bears eyes, tentacles, and sensory palps. The peristomium surrounds the mouth and may bear setae, palps, or, in predatory forms, chitinous jaws. Ciliary feeders may bear a crown of tentacles that can be opened like a fan or withdrawn into the tube.

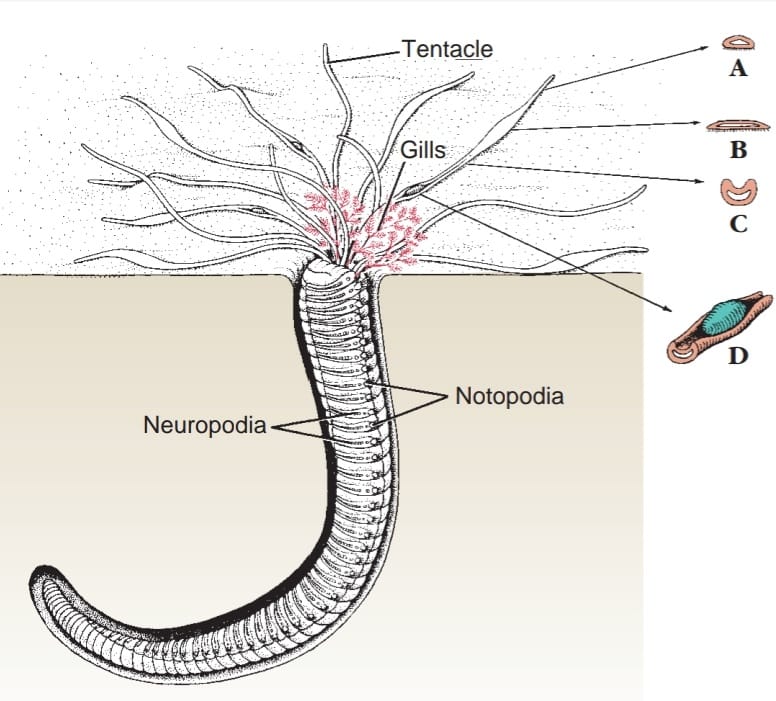

The polychaete trunk is segmented, and most segments bear parapodia, which may have lobes, cirri, setae, and other parts on them. Parapodia are used in crawling, swimming, or for anchoring the animal in its tube. They usually serve as the chief respiratory organs, although some polychaetes also have gills. Amphitrite (Gr. a mythical sea nymph), for example, has three pairs of branched gills and long extensible tentacles. Arenicola (L. arena, sand, colo, inhabit), the burrowing lugworm, has paired gills on certain segments.

Nutrition

A polychaete’s digestive system consists of a foregut, a midgut, and a hindgut. The foregut includes a stomodeum, a pharynx, and an anterior esophagus. It is lined with cuticle, and the jaws, where present, are constructed of cuticular protein. The more anterior portions of the midgut secrete digestive enzymes but absorption takes place toward the posterior end. A short hindgut connects the midgut to the exterior via the anus, which is on the pygidium. Errant polychaetes are typically predators and scavengers. Sedentary polychaetes feed on suspended particles, or they may be deposit feeders, consuming particles on or in the sediment.

Circulation and Respiration

Polychaetes show considerable diversity in both circulatory and respiratory structures. As previously mentioned, parapodia and gills serve for gaseous exchange in various species. However, in some polychaetes there are no special organs for respiration, and gaseous exchange takes place across the body surface. The circulatory pattern varies greatly. In Nereis a dorsal longitudinal vessel carries blood anteriorly, and a ventral longitudinal vessel conducts it posteriorl.

Blood flows between these two vessels via segmental networks in the parapodia, septa, and around the intestine. In the burrowing predatory worm Glycera (Gr. Glykera, a feminine proper name) the circulatory system is reduced and joins directly with the coelom. Septa are incomplete, and thus the coelomic fluid assumes the function of circulation. Many polychaetes have respiratory pigments such as hemoglobin, chlorocruorin, or hemerythrin.

Excretion

Excretory organs consist of protonephridia and mixed proto- and metanephridia in some, but most polychaetes have metanephridia. There is one pair per segment, with the inner end of each (nephrostome) opening into a coelomic compartment. Coelomic fluid passes into the nephrostome, and selective resorption occurs along the nephridial duct.

Nervous System and Sense Organs

Organization of the central nervous system in polychaetes follows the basic annelid plan. Dorsal cerebral ganglia connect with a subpharyngeal ganglion via a circum pharyngeal connective. A double ventral nerve cord courses the length of the worm, with metamerically arranged ganglia.

Sense organs are highly developed in polychaetes and include eyes, nuchal organs, and statocysts. Eyes, when present, may range from simple eyespots to well-developed organs. Eyes are most conspicuous in errant worms. Usually the eyes are retinal cups, with rodlike photoreceptor cells (lining the cup wall) directed toward the lumen of the cup. The highest degree of eye development occurs in the family Alciopidae, which has large, image resolving eyes similar in structure to those of some cephalopod molluscs with cornea, lens, retina, and retinal pigments.

Alciopid eyes also have accessory retinas, a characteristic independently evolved by deep-sea fishes and some deep-sea cephalopods. The accessory retinas of alciopids are sensitive to different wavelengths. The eyes of these pelagic animals may be well adapted to function because penetration by the different wavelengths of light varies with depth. Studies with electroencephalograms show that they are sensitive to dim light of the deep sea. Nuchal organs are ciliated sensory pits or slits that appear to be chemoreceptive, an important factor in food gathering. Some burrowing and tube-building polychaetes have statocysts that function in body orientation.

Useful External Links

- Polychaete chaetae: Function, fossils, and phylogeny by Sarah Woodin

- A Review of “Polychaeta” Chemicals and their Possible Ecological Role by Marina Coutinho

- Global diversity of polychaetes (Polychaeta; Annelida) in freshwater Tarmo Timm