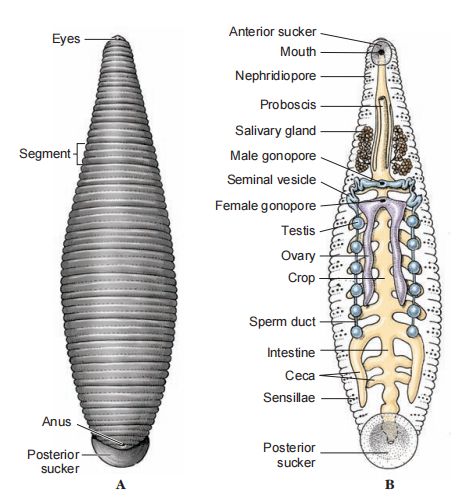

Class Hirudinida is divided into three orders, Hirudinea, the “true” leeches, and two others that merit mention here because their members are morphological intermediates between oligochaetes and true leeches. Oligochaetes have variable numbers of segments, segments bear setae, and there are no suckers on the body. True leeches have 34 segments, entirely lack setae, and possess anterior and posterior suckers. Members of order Acanthobdellida have 27 segments, bear setae on the first five segments, and have a posterior sucker. Members of order Branchiobdellida have 14 or 15 segments, no setae, and an anterior sucker. Branchiobdellids are commensal or parasitic on crayfish. Hereafter, leech refers to members of order Hirudinea.

Leeches occur predominantly in freshwater habitats, but a few are marine, and some have even adapted to terrestrial life in warm, moist places. They are more abundant in tropical countries than in temperate zones. Most leeches are between 2 and 6 cm in length, but some, including “medicinal” leeches, reach 20 cm. The giant of all is the Amazonian Haementeria (Gr. haimateros, bloody), which reaches 30 cm. Leeches are usually flattened dorsoventrally and exhibit a variety of patterns and colors: black, brown, red, or olive green.

Many leeches live as carnivores on small invertebrates; some are temporary parasites; and some are permanent parasites, never leaving their host. Some leeches attack human beings and are a nuisance to outdoor enthusiasts. Like oligochaetes, leeches are hermaphroditic and have a clitellum, which appears only during breeding season. The clitellum secretes a cocoon for reception of eggs.

Form and Function

Unlike other annelids, leeches have a fixed number of segments but they appear to have many more because each segment is marked by transverse grooves to form superficial rings. Unlike other annelids, leeches lack distinct coelomic compartments. In all but one species the septa have disappeared, and the coelomic cavity is filled with connective tissue and a system of spaces called lacunae. The coelomic lacunae form a regular system of channels filled with coelomic fluid, which in some leeches serves as an auxiliary circulatory system.

Leeches are more highly specialized than oligochaetes. They have lost the setae used by oligochaetes in locomotion and have developed suckers for attachment while sucking blood (their gut is specialized for storage of large quantities of blood). Most leeches crawl with looping movements of the body, by attaching first one sucker and then the other and pulling the body along the surface. Aquatic leeches swim with a graceful undulatory movement.

Nutrition

Leeches are popularly considered parasitic, but many are predaceous. Most freshwater leeches are active predators or scavengers equipped with a proboscis that can be extended to ingest small invertebrates or to take blood from cold-blooded vertebrates. Some can force their pharynx or proboscis into soft tissues such as the gills of fish. Some terrestrial leeches feed on insect larvae, earthworms, and slugs, which they hold by an oral sucker while using a strong sucking pharynx to ingest food. Other terrestrial forms climb bushes or trees to reach warm-blooded vertebrates such as birds or mammals.

Most leeches are fluid feeders. Many prefer to feed on tissue fluids and blood pumped from open wounds. Some freshwater leeches are true bloodsuckers, preying on cattle, horses, humans, and other mammals. True bloodsuckers, which include the so-called medicinal leech, Hirudo medicinalis (L. hirudo, a leech), have cutting plates, or chitinous “jaws,” for cutting through tough skin. Some parasitic leeches leave their hosts only during the breeding season, and certain fish parasites are permanently parasitic, depositing their cocoons on their host fish. However, even the true bloodsuckers rarely remain on the host for a long period of time.

For centuries “medicinal leeches” (Hirudo medicinalis) were used for bloodletting because of the mistaken idea that a host of bodily disorders and fevers were caused by an excess of blood. A 10- to 12-cm-long leech can extend to a much greater length when distended with blood, and the amount of blood it can suck is considerable. Leech collecting and leech culture in ponds were practiced in Europe on a commercial scale during the nineteenth century. Wordsworth’s poem “The Leech-Gatherer” was based on this use of leeches.

Leeches are once again being used medically. When fingers, toes, or ears are severed, microsurgeons can reconnect arteries but not all the more delicate veins. Leeches are used to relieve congestion until the veins can grow back into the healing appendage.

Respiration and Excretion Gas exchange occurs only through the skin except in some fish leeches, which have gills. There are 10 to 17 pairs of nephridia, in addition to coelomocytes and certain other specialized cells that also may be involved in excretory functions.

Nervous and Sensory Systems

Leeches have two “brains”: one is anterior and composed of six pairs of fused ganglia (forming a ring around the pharynx), the other is posterior and composed of seven pairs of fused ganglia. An additional 21 pairs of segmental ganglia occur along the double nerve cord. In addition to free sensory nerve endings and photoreceptor cells in the epidermis, there is a row of sense organs, called sensillae, in the central annulus of each segment. Pigment-cup ocelli also are present in many species.

Leeches are highly sensitive to stimuli associated with the presence of a prey or host. They are attracted by and will attempt to attach to an object smeared with appropriate host substances, such as fish scales, oil secretions, or sweat. Those that feed on the blood of mammals are attracted by warmth; terrestrial haemadipsids of the tropics will converge on a person standing in one place.

Reproduction Leeches are hermaphroditic but cross-fertilize during copulation. Sperm are transferred by a penis or by hypodermic impregnation (a spermatophore is expelled from one worm and penetrates the integument of the other). After copulation their clitellum secretes a cocoon that receives eggs and sperm. Leeches may bury their cocoons in mud, attach them to submerged objects, or, in terrestrial species, place them in damp soil. Development is similar to that of oligochaetes.

Circulation The coelom of leeches has been reduced by the invasion of connective tissue and, in some, by a proliferation of chloragogen tissue, to a system of coelomic sinuses and channels. Some orders of leeches retain a typical oligochaete circulatory system, and in these the coelomic sinuses act as an auxiliary blood vascular system. In other orders the traditional blood vessels are lacking and the system of coelomic sinuses forms the only blood vascular system. In those orders contractions of certain longitudinal channels provide propulsion for the blood (the equivalent of coelomic fluid).

Useful External Links

- Annelida, Hirudinida (Leeches) by William Moser

- A new species of medicinal leech in the genus Hirudo Linnaeus, 1758 (Hirudiniformes, Hirudinidae) from Tianjin City, China by Si-Jie Jin

- A new species of Hirudo (Annelida: Hirudinidae): historical biogeography of Eurasian medicinal leeches by Daniel H. Shain