Arachnids (Gr. arachne¯, spider) exhibit enormous anatomical variation. In addition to spiders, the group includes scorpions, pseudoscorpions, whip scorpions, ticks, mites, daddy longlegs (harvestmen), and others. There are many differences among these taxa with respect to form and appendages. They are mostly free-living and are most common in warm, dry regions. Arachnids have become extremely diverse: More than 80,000 species have been described to date. They were among the first arthropods to move into terrestrial habitats. For example, scorpions are among Silurian fossils, and by the end of the Paleozoic period mites and spiders had appeared.

All arachnids have two tagmata: a cephalothorax (head and thorax) and an abdomen, which may or may not be segmented. The abdomen houses the reproductive organs and respiratory organs such as tracheae and book lungs. The cephalothorax usually bears a pair of chelicerae, a pair of pedipalps, and four pairs of walking legs. Most arachnids are predaceous and have fangs, claws, venom glands, or stingers; fangs are modified chelicerae, whereas claws (chelae) are modified pedipalps. They usually have a strong sucking pharynx with which they ingest the fluids and soft tissues from the bodies of their prey. Among their interesting adaptations are spinning glands of spiders.

Most arachnids are harmless to humans and actually do much good by destroying injurious insects. Arachnids typically feed by releasing digestive enzymes over or into their prey and then sucking the predigested liquid. A few, such as black widow and brown recluse spiders, can give dangerous bites. Stings of scorpions may be quite painful, and those of a few species can be fatal. Some ticks and mites are carriers of diseases as well as causes of annoyance and painful irritations. Certain mites damage a number of important food and ornamental plants by sucking their juices. Several smaller orders are not included in our discussion.

Order Araneae: Spiders

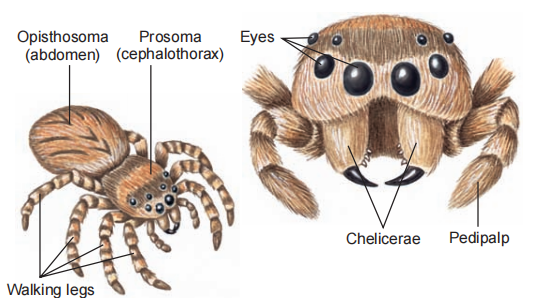

Spiders are a large group of arachnids comprising about 40,000 species distributed throughout the world. The spider body is compact: a cephalothorax (prosoma) and abdomen (opisthosoma), both unsegmented and joined by a slender pedicel. A few spiders have a segmented abdomen, which is considered an ancestral character.

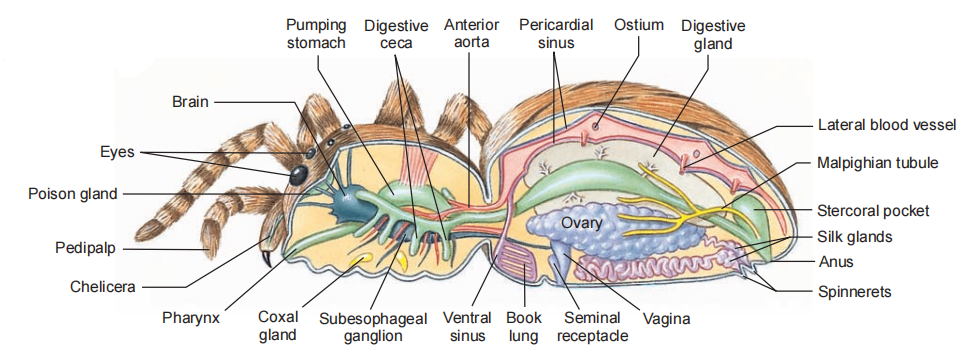

Anterior appendages include a pair of chelicerae, which have terminal fangs through which run ducts from venom glands, and a pair of leglike pedipalps, which have sensory function and are also used by males to transfer sperm. The basal parts of pedipalps may be used to manipulate food. Four pairs of walking legs terminate in claws.

All spiders are predaceous, feeding largely on insects, which they effectively dispatch with poison from their fangs. Some spiders chase prey; others ambush them; and many trap them in a net of silk. After a spider seizes prey with its chelicerae and injects venom, it liquefies the prey’s tissues with digestive fluid and sucks the resulting broth into its stomach. Spiders with teeth at the bases of chelicerae crush or chew prey, aiding digestion by enzymes from their mouth.

Spiders breathe by means of book lungs or tracheae or both. Book lungs consist of many parallel air pockets extending into a blood-filled chamber. Air enters the chamber by a slit in the body wall. Tracheae form a system of air tubes that carry air directly to the blood from an opening called a spiracle. The tracheae are similar to those in insects but are much less extensive and have evolved independently in both arthropod lineages. The tracheal systems of arthropods thus represent a case of massive evolutionary convergence.

Spiders and insects have also independently evolved a unique excretory system of Malpighian tubules, which work in conjunction with specialized resorptive cells in the intestinal epithelium. Potassium and other solutes and waste materials are secreted into the tubules, which drain the fluid, or “urine,” into the intestine. Resorptive cells recapture most potassium and water, leaving behind such wastes as uric acid. This recycling of water and potassium allows species living in dry environments to conserve body fluids by producing a nearly dry mixture of urine and feces. Many spiders also have coxal glands, which are modified nephridia that open at the coxa, or base, of the first and third walking legs.

Spiders usually have eight simple eyes, each with a lens, optic rods, and a retina. They are used chiefly for perception of moving objects, but some, such as those of hunting and jumping spiders, may form images. Since a spider’s vision is often poor, its awareness of its environment depends largely on cuticular mechanoreceptors, such as sensory setae (sensilla). Fine setae covering the legs can detect vibrations in the web, struggling prey, or even air movements.

Web-Spinning Habits The ability to spin silk is central to a spider’s life, as it is in some other arachnids such as tetranychid spider mites. Two or three pairs of spinnerets containing hundreds of microscopic tubes run to special abdominal silk glands. A scleroprotein secretion emitted as a liquid from the spinnerets hardens to form a silk thread. Threads of spider silk are stronger than steel threads of the same diameter and second in strength only to fused quartz fibers.

Many species of spiders spin silk webs. The kind of net varies among species. Some webs are simple and consist merely of a few strands of silk radiating out from a spider’s burrow or place of retreat. Others spin beautiful, geometrical orb webs. However, spiders use silk threads for many additional purposes: nest lining, sperm webs or egg sacs, bridge lines, draglines, warning threads, molting threads, attachment discs, nursery webs, and for wrapping prey items. Not all spiders spin webs for traps. Some spiders throw a sticky bolus of silk to capture their prey. Others, such as wolf spiders, jumping spiders, and fisher spiders, simply chase and catch their prey. These spiders likely lost the ability to produce silk for prey capture.

minnow. This handsome spider feeds mostly on aquatic and terrestrial insects but occasionally captures small fishes and tadpoles. It pulls its paralyzed victim from the water, pumps in digestive enzymes, then sucks out the

predigested contents.

Reproduction A courtship ritual visually precedes mating. Before mating, a male spins a small web, deposits a drop of sperm on it, and then picks up the sperm to be stored in special cavities of his pedipalps. When he mates, he inserts his pedipalps into the female genital opening to store the sperm in his mate’s seminal receptacles. A female lays her eggs in a silken net, which she may carry or attach to a web or plant. A cocoon may contain hundreds of eggs, which hatch in approximately two weeks. Young usually remain in the egg sac for a few weeks and molt once before leaving it. The number of molts may vary, but typically ranges between four and twelve before adulthood is reached.

Are Spiders Really Dangerous? It is amazing that such small and innocuous creatures have generated so much unreasonable fear in human minds. Spiders are timid creatures that, rather than being dangerous enemies to humans, are actually allies in the continuing battle with insects and other arthropod pests. Venom produced to kill prey is usually harmless to humans. The most poisonous spiders bite only when threatened or when defending their eggs or young. Even American tarantulas despite their fearsome size, are not dangerous. They rarely bite, and their bite is about as serious as a bee sting.

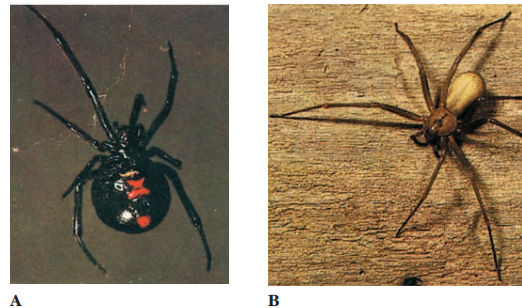

There are, however, two genera in the United States that can give severe or even fatal bites: Latrodectus (L. latro, robber, + dectes, biter; black widow, five species) and Loxosceles (Gr. loxos, crooked, + skelos, leg; brown recluse, 13 species). Black widows are moderate to small in size and shiny black, usually with a bright orange or red spot, commonly in the shape of an hourglass, on the underside of their abdomen. Their venom is neurotoxic, acting on the nervous system. About four or five of every 1000 reported bites are fatal.

Brown recluse spiders are brown and bear a violin-shaped dorsal stripe on their cephalothorax. Their venom is hemolytic rather than neurotoxic, producing death of tissues and skin surrounding the bite. Their bite can be mild to serious and occasionally fatal to small children and older individuals.

Note the red “hourglass” on the ventral side of her abdomen. B, Brown recluse spider, Loxosceles reclusa, is a small venomous spider. Note the small violin-shaped marking on its cephalothorax. The venom is hemolytic and dangerous.

Some spiders in other parts of the world are also dangerous, for example, funnelweb spiders Atrax spp. in Australia. Most dangerous of all are spiders in the South and Central American genus Phoneutria. They are large (10 to 12 cm leg span) and quite aggressive. Their venom is among the most pharmacologically toxic of spider venoms, and their bites cause intense pain, neurotoxic effects, sweating, acute allergic reaction, and non sexual enlargement of the penis.

Bristowe ( The World of Spiders. 1971 Rev. ed. London, Collins) estimated that at certain seasons a field in Sussex, England (that had been undisturbed for several years) had a population of 2 million spiders to the acre. He concluded that so many spiders could not successfully compete except for the many specialized adaptations they had evolved. These include adaptations to cold and heat, wet and dry conditions, and light and darkness.

Some spiders capture large insects, some only small ones; web builders snare mostly flying insects, whereas hunters seek those that live on the ground. Some lay eggs in the spring, others in the late summer. Some feed by day, others by night, and some have developed flavors that are distasteful to birds or to certain predatory insects. As it is with spiders, so has it been with other arthropods; their adaptations are many and diverse and contribute in no small way to their long success.

Useful External Links

- What Are Arachnids? by Debbie Hadley

- Arachnids by Robert K Colwell

- Phylum Arthropoda: Introduction and Arachnida by D. Christopher Rogers