Lampreys share with gnathostomes a more advanced kidney than hagfish, a pho-tosensitive pineal, a lateral line, radial muscles in the fins, functional eyes, extrin-sic eye muscles, neural and hemal vertebral elements formed around the notochord, and similarities in pituitary histology. These features have strongly suggested to some that hagfish is the sister group to lampreys and gnathostomes together. The ear, however, has only two semi-circular canals. Like teleosts, in the sea their blood is hypotonic and in freshwater hypertonic.

All lampreys are elongate and eel-like; the largest species is almost a meter long, with seven external gill openings, a single opening to the nasohypophyseal sac, and a kind of spiral valve in the ciliated intestine. The Upper Carboniferous fossil Hardistiella is similar to living forms, and it remains unclear how (or, indeed, whether) they are related to cephalaspid or anaspid fossil agnathans. Although living forms have an entirely cartilaginous skeleton, with a few cartilaginous “vertebral” elements around the massive unconstricted notochord, under experimental conditions lam-prey cartilage retains the ability to become calcified and so the present lack of calcification seems secondary, and is not a bar to a link with the heavily min-eralized fossil agnathans.

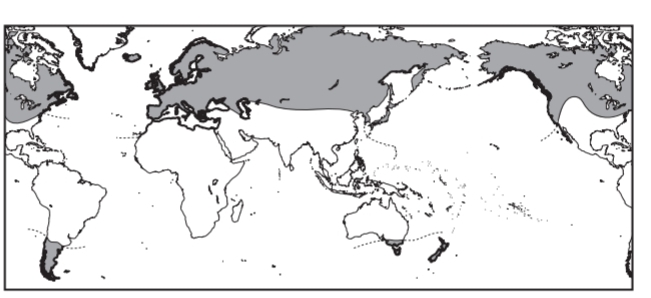

There are today some 40 or so lamprey species, found in rivers north and south of latitudes 30° north and south, interestingly divided into larger parasitic and smaller non-parasitic species (some not even feed-ing as adults). All lay small eggs in redds scraped in the gravel of streams and rivers, which hatch into ammocoete larvae that bury in mud.

The ammo-coetes pump water through the pharynx and filter-feed by using endostylar mucus to trap particles. They spend a quiet 5–7 years in the mud before undergoing a radical metamorphosis and swimming out. The adults either spawn in the river soon after metamorphosis, or, like Geotria australis and Petromyzon marinus, pass down to spend some years in the sea before returning to the river to spawn. In the sea (or in the Great Lakes for the landlocked P. marinus) they rasp the skin of other fishes and feed on their blood. P. marinus hitches lifts on dolphins and basking sharks, feeding on the urea-rich blood of the shark thanks to special urea-secreting capabili-ties.

endostyle below gill pouches. After de Beer (1928).

Non-parasitic species perhaps evolved from their “twin” parasitic species as a result of isolation in parts of river systems where host fishes were rare; these species do not descend to the sea. There are even examples of parasitic and non-parasitic races of the same species, and evolutionary aspects of lamprey systematics are of continuing interest.