Until fairly recently, myxinoids and lampreys were regarded as being sepa-rately derived from fossil agnathan groups, but some workers provided mor-phological evidence for their closer relationship (e.g. Yalden, 1985), and the advent of molecular taxonomy has supported this, so they now lie together for most ichthyologists as a sister group to all other craniates. A single fossil hagfish (Myxinikela) is known from the upper Carboniferous (330mya), and looks much like the living forms, if fatter.

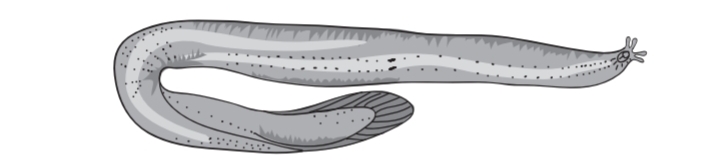

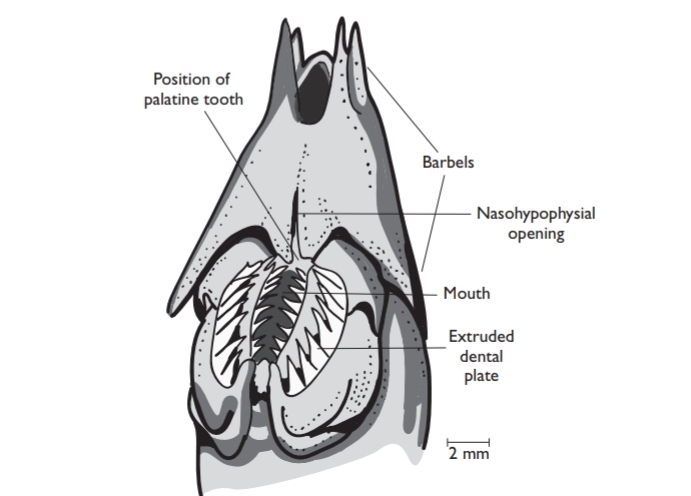

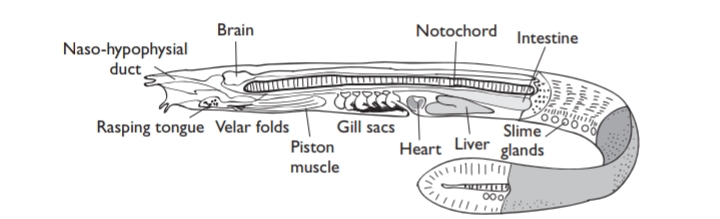

Hagfish are naked and eel-like, scavenge on dead and dying fishes, and invertebrates with a rasping tongue. In several features they are different from other vertebrates. First of all, they have no vertebrae! There is only a single semi-circular canal, the blood is isosmotic with seawater, and vast quantities of tenacious slime can be produced from special thread cells opening along the body. This unique mechanism (a single hagfish can solidify a bucket of water with its slime) acts both defensively and prevents others from sharing hagfish food.

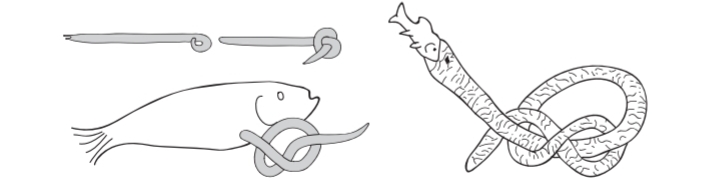

It is complemented by the ability of hagfish to tie themselves into a knot which is slid along the body to wipe off the slime. Knotting is also used to escape capture, and (as with the more complex knots made by Moray eels) to tear off food. There are up to 16 pairs of external gill openings and a single olfactory capsule with an exhalent duct to the pharynx. The eyes lack eye muscles and are buried below the skin.

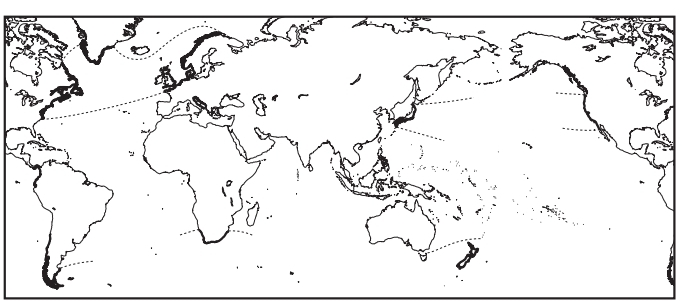

Hagfish lay large yolky eggs, and, in contrast to lampreys, development is direct with-out a larval stage. Around 50 living species of hagfish (all marine) live in tem-perate seas, down to 2000 m.