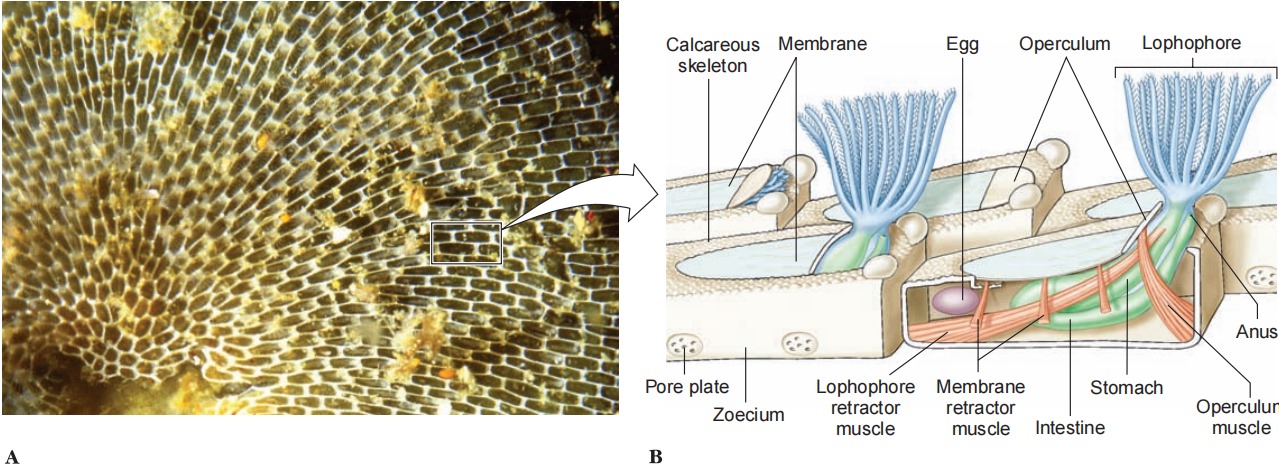

Ectoprocta (ek-to-prok’ – ta) (Gr. ektos, outside, + proktos, anus) contains aquatic animals that often encrust hard surfaces. Most species are sessile, but some slide slowly, and others crawl actively, across the surfaces they inhabit. With very few exceptions, they are colony builders. Each member of a colony is small, typically less than 0.5 mm. Colony members, called zooids, feed by extending their lophophores into surrounding water to collect tiny particles. Zooids secrete small containers in which they live and thus form an exoskeleton. The exoskeleton or zoecium, may, according to species, be gelatinous, chitinous, or stiffened with calcium and possibly also impregnated with sand. Its shape may be boxlike, vaselike, oval, or tubular.

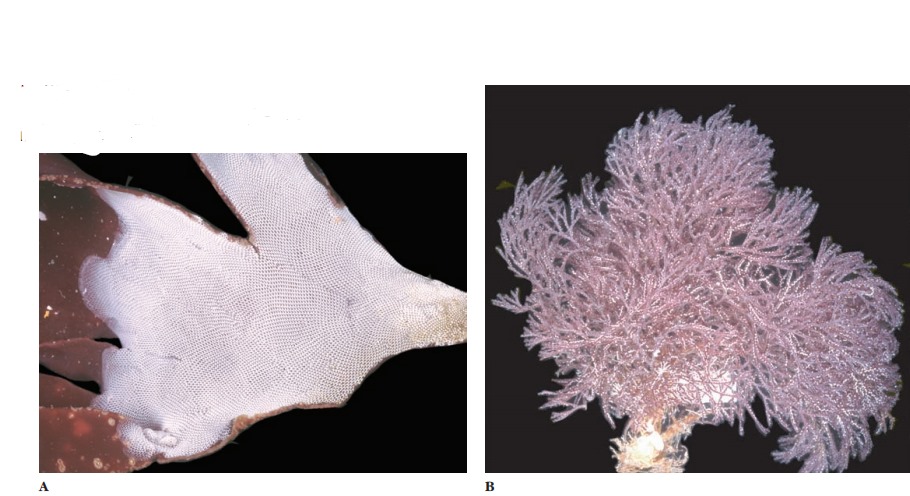

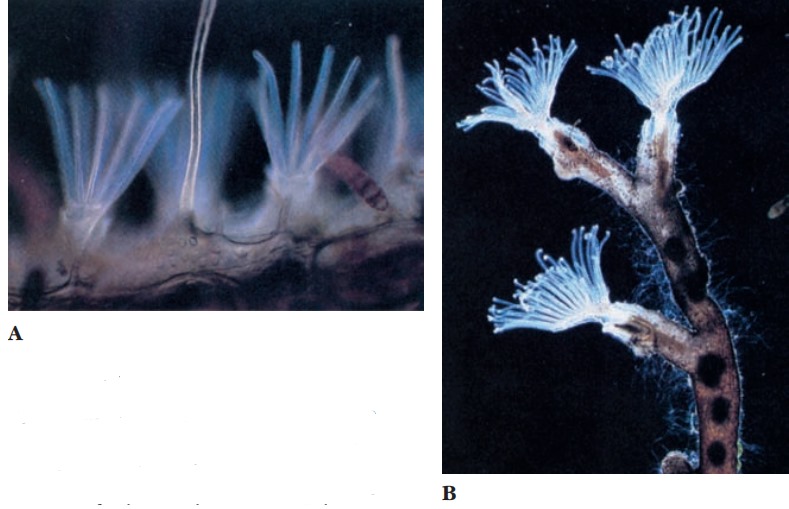

Ectoprocts have left a rich fossil record since the Ordovician period and are diverse and abundant today. There are about 4500 living species of ectoprocts. They live in both freshwater and marine habitats but largely in shallow waters. Some colonies form limy encrustations on seaweed, shells, and rocks; others form fuzzy or shrubby growths or erect, branching colonies that look like seaweed. Some ectoprocts might easily be mistaken for hydroids but can be distinguished under a microscope by presence of an anus .

Although zooids are minute, the colonies are often several centimeters in diameter; some encrusting colonies may be a meter or more in width, and erect forms may reach 30 cm or more in height. Marine forms exploit all kinds of firm surfaces, such as shells, rocks, large brown algae, mangrove roots, ship bottoms, and even the bottoms of icebergs! Freshwater ectoprocts may form mosslike colonies on stems of plants or on rocks, usually in shallow ponds or pools. In some freshwater forms individuals are borne on finely branching stolons that form delicate tracings on the underside of rocks or plants. Other freshwater ectoprocts are embedded in large masses of gelatinous material

Ectoprocts have long been called bryozoans, or moss animals (Gr. bryon, moss, + zoon, animal), a term that originally included Entoprocta also. However, because entoprocts have their anu located within the tentacular crown, they are commonly separated from ectoprocts, which, like other lophophorates, have their anus outside the circle of tentacles. Many authors continue to use the name “Bryozoa” but exclude entoprocts from the group.

Each member of a colony lives in a tiny chamber, called a zoecium, which is secreted by its epidermis . Each zooid consists of a feeding polypide and a case-forming cystid. A polypide includes the lophophore, digestive tract, muscles, and nerve centers. A cystid includes the body wall of an animal, together with its secreted exoskeleton.

Polypides live a type of jack-in-the-box existence, popping up to feed but, at the slightest disturbance, quickly withdrawing into their little chamber, which often has a tiny trapdoor (operculum) that shuts to conceal its inhabitant. To extend its tentacular crown, certain muscles contract, which increases hydrostatic pressure within the body cavity and pushes the lophophore out by a hydraulic mechanism. Other muscles can contract to withdraw the crown to safety with great speed.

When feeding, an animal extends its lophophore and spreads its tentacles to form a funnel. Cilia on the tentacles draw water into the funnel and out between the tentacles. Food particles caught by cilia in the funnel are drawn into the mouth, both by a pumping action of the muscular pharynx and by action of cilia along the length of the tentacles and in the pharynx itself. Undesirable particles can be rejected by reversing the ciliary action, by drawing the tentacles close together, or by retracting the whole lophophore into the zoecium. The lophophore ridge tends to be circular in marine ectoprocts and U-shaped in freshwater species. A septum divides the mesocoel in the lophophore from the larger posterior metacoel. A pro-tocoel and epistome occur only in freshwater ectoprocts.

Digestion in the ciliated, U-shaped digestive tract begins extracellularly in the stomach and is completed intracellularly in the intestine. Respiratory, vascular, and excretory organs are absent. Gaseous exchange is through the body surface, and since ectoprocts are small, coelomic fluid is adequate for internal transport. Pores in the walls between adjoining zooids permit exchange of materials throughout the colony by way of the coelomic fluid. Coelomocytes engulf and store waste materials. A ganglionic mass and a nerve ring surround the pharynx, but no specialized sense organs are present.

Most colonies contain only feeding individuals, but specialized zooids incapable of feeding (collectively called heterozooids) occur in some species. One type of modified zooid (called an avicularium) resembles a bird beak that snaps at small invading organisms that might foul a colony. Another type (called a vibraculum) has a long bristle that apparently helps to sweep away foreign particles. Most ectoprocts are hermaphroditic. Some species shed eggs into seawater, but most brood their eggs, some within the coelom and some externally in a special brood chamber called an ovicell, which is a modifi ed zoecium in which an embryo develops.

In some cases many embryos proliferate asexually from that initial embryo in a process called polyembryony. Cleavage is radial but apparently mosaic. Little is known of mesoderm derivation. Larvae of nonbrooding species have a functional gut and swim for a few months before settling; larvae of brooding species do not feed and settle after a brief free-swimming existence. They attach to the substratum by secretions from an adhesive sac, then metamorphose to their adult form.

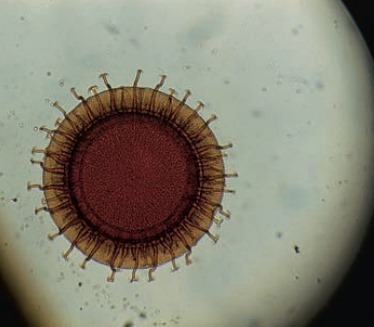

Each colony begins from this single metamor phosed primary zooid, which is called an ancestrula. The ancestrula then undergoes asexual budding to produce the many zooids of a colony. Freshwater ectoprocts have another type of budding that produces statoblasts , which are hard, resistant capsules containing a mass of germinative cells. Statoblasts are formed during summer and fall. When a colony dies in late autumn, statoblasts remain, and in spring they give rise to new polypides and eventually to new colonies.

Useful External Links

- The Phylum Bryozoa: From Biology to Biomedical Potential by Robert Kiss

- The first comprehensive molecular phylogeny of Bryozoa (Ectoprocta) based on combined analyses of nuclear and mitochondrial genes by Matthias Obst

- Key novelties in the evolution of the aquatic colonial phylum Bryozoa: evidence from soft body morphology by Andreas Wanninger