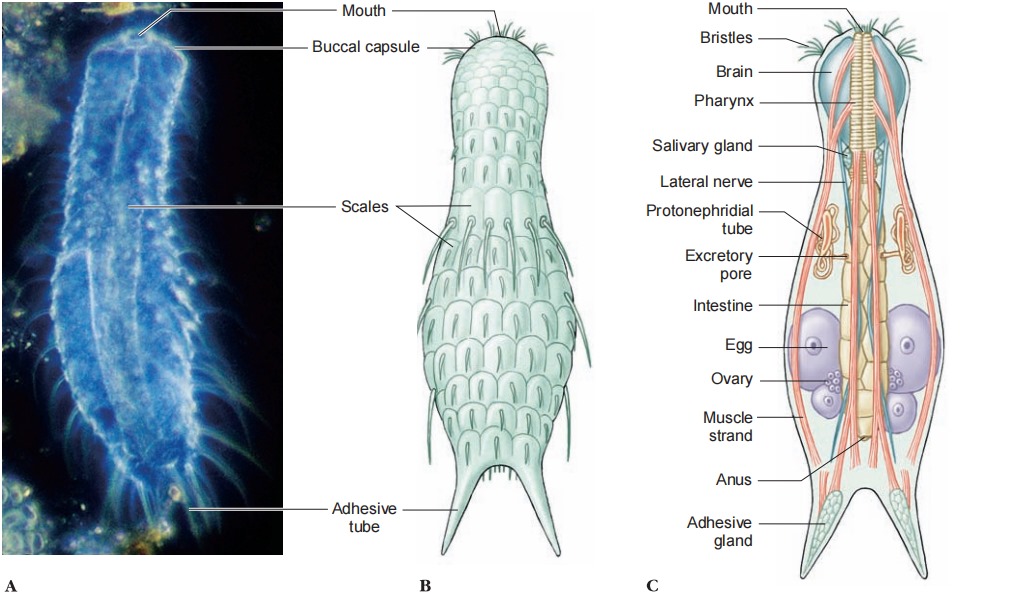

Gastrotricha ( gas-tro-tri’ -ka) (N. L. fr. Gr. gaster, gastros, stomach or belly, + thrix, trichos, hair) includes small, ventrally flattened animals usually less than 1 mm in length. The largest species of gastrotrichs can reach lengths of about 3 mm. Superficially, gastrotrichs may appear somewhat like rotifers but lacking a corona and mastax and having a characteristically bristly or scaly body. They are usually found gliding on the substrate, or the surface of an aquatic plant or animal, by means of their ventral cilia, or they compose part of the meiofauna in interstitial spaces between substrate particles.

Gastrotrichs occur in fresh, brackish, and salt water. The 450 or so species are about equally divided between these environments. Many species are cosmopolitan, but only a few occur in both freshwater and the sea. Much is yet to be learned about their distribution and biology.

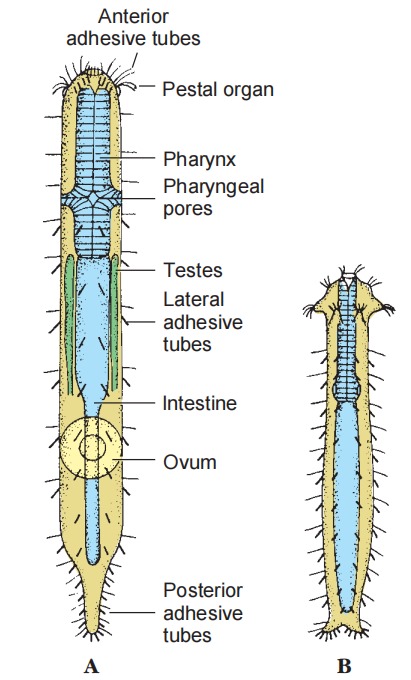

A gastrotrich is usually elongated, with a convex dorsal surface bearing a pattern of bristles, spines, or scales, and a flattened ciliated ventral surface. Cells on the ventral surface may be monociliated or multiciliated. The head is often lobed and ciliated, and the tail end may be greatly elongated or forked in some species. A partially syncytial epidermis is found beneath the cuticle; it has some cellular regions. Longitudinal muscles are better developed than are circular ones, and in most cases they are unstriated. Adhesive tubes secrete a substance for attachment. A dual-gland system for attachment and release resembles that described for Turbellaria.

No specialized respiratory or circulatory structures occur in gastrotrichs; gas exchange is by simple diffusion in these tiny animals. At least some species appear capable of anaerobic respiration. Their digestive system is complete and comprises a mouth, a muscular pharynx, a stomach-intestine, and an anus.

Food is largely algae, protozoa, bacteria, and detritus, which are directed to their mouth by their head cilia. Digestion appears to be extracellular, although little is known about the exact mechanisms of digestion and nutrient absorption. Protonephridia are equipped with solenocytes rather than flame cells. Solenocytes have a single flagellum enclosed in a cylinder of cytoplasmic rods as opposed to the many flagella found in flame bulbs. There is no body cavity in gastrotrichs, and the internal organs are all packed tightly into the compact body.

Their nervous system includes a brain near the pharynx and a pair of lateral nerve trunks. Sensory structures are similar to those in rotifers, except that eyespots are generally lacking although some species have pigmented eyespots (ocelli) in the brain. Sensory bristles, often concentrated on the head, are

modifi ed from cilia and are primarily tactile.

Gastrotrichs are typically hermaphroditic, although the male system of some is so rudimentary that they are functionally par- thenogenetic females. Like rotifers, some gastrotrichs produce thin-walled, rapidly developing eggs and thick-shelled, dormant eggs. The thick-shelled eggs can withstand harsh environments and may survive dormancy for some years. Cleavage is not well studied but appears to be radial. Development is direct, and juveniles have the same form as adults. Growth and maturation are often rapid, and newly hatched juveniles usually reach sexual maturity within just a few days.

Useful External Links