Rotifers are dioecious, and males are usually smaller than females. However, despite having separate sexes, males are entirely unknown in the class Bdelloidea, and in the Monogononta they seem to occur only for a few weeks of the year. The female reproductive system in the Bdelloidea and Monogononta consists of combined ovaries and yolk glands (germovitellaria) and oviducts that open into the cloaca. Yolk is supplied to developing ova by flow-through cytoplasmic bridges, rather than as separate yolk cells as in ectolecithal Platythelminthes.

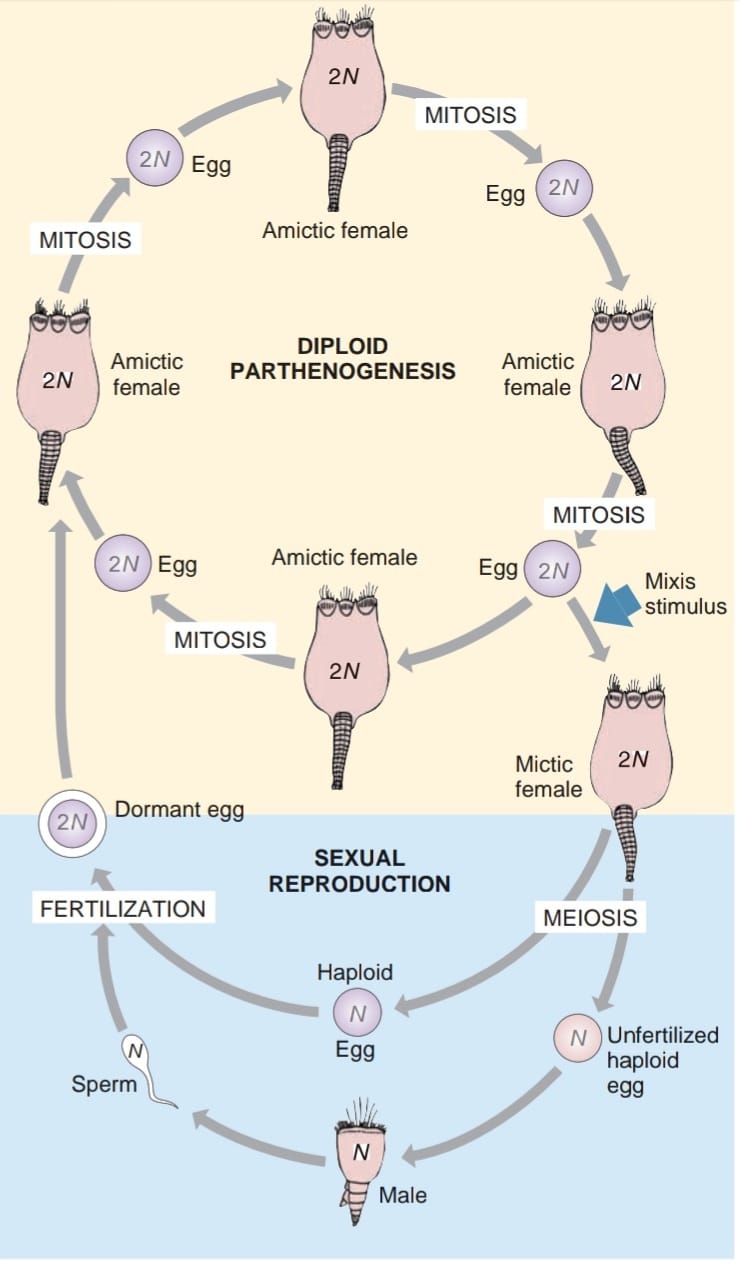

In Bdelloidea ( Philodina, for example), all females are parthenogenetic and produce diploid eggs that hatch into diploid females. These females reach maturity in a few days. In class Seisonidea females produce haploid eggs that must be fertilized and that develop into either males or females. In Monogononta, however, females produce two kinds of eggs . During most of the year diploid females produce thin-shelled, diploid amictic eggs. Amictic eggs develop parthenogenetically into diploid (amictic) females. However, such rotifers often live in temporary ponds or streams and are cyclic in their reproductive patterns.

Any one of several environ mental factors—for example, crowding, diet, or photo-period (according to species)may induce amictic eggs to develop into diploid mictic females that produce thin-shelled haploid eggs. If these eggs are not fertilized, they develop into haploid males. But if fertilized, the eggs, called mictic eggs, develop a thick, resistant shell and become dormant. They survive over winter (“winter eggs”) or until environmental conditions are again suitable, at which time they hatch into amictic females. Dormant eggs are often dispersed by winds or birds, which may explain the peculiar distribution patterns of rotifers.

The male reproductive system includes a single testis and a ciliated sperm duct that runs to a genital pore (males usually lack a cloaca). The end of the sperm duct is specialized as a copulatory organ. Copulation is usually by hypodermic impregnation; the penis can penetrate any part of a female’s body wall and inject sperm directly into her pseudocoel. The zygote undergoes modified spiral cleavage. Females hatch with adult features, needing only a few days’ growth to reach maturity. Males often do not grow and are sexually mature at hatching.

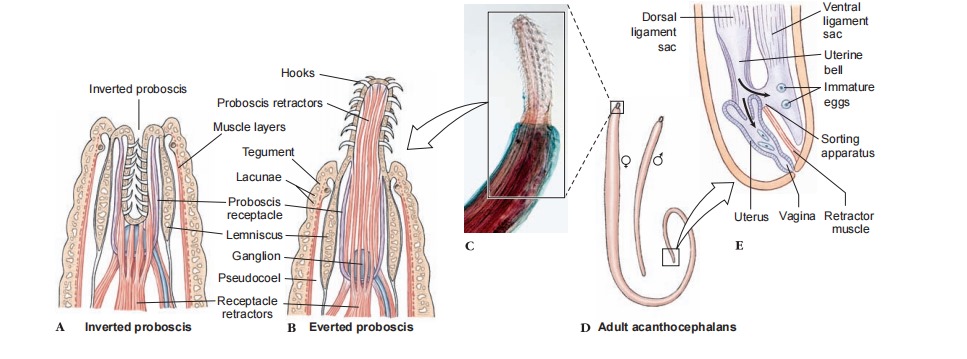

Members of phylum Acanthocephala (a-kan ‘-tho-sef ‘a-la) (Gr.akantha, spine or thorn, + kephale¯, head) are commonly called“spiny-headed worms.” The phylum derives its name from one ofits most distinctive features, a cylindrical, invaginable proboscis bearing rows of recurved spines, by which it attaches itself to the intestine of its host .

The phylum is cosmopolitan, and more than 1100 species are known, most of which parasitize fish, birds, and mammals. All acanthocephalans are endoparasitic, living as adults in the intestine of vertebrates. Larvae of spiny-headed worms develop in arthropods, either crustaceans or insects, depending on the species. Various species range in size from less than 2 mm to more than 1 m in length. Females of a species are usually larger than males. Their body is usually bilaterally flattened, with numerous transverse wrinkles. Worms are typically cream color but may absorb yellow or brown pigments from the intestinal contents.

Useful External Links