Approximately 25,000 species of Nematoda (nem-a-to´da) (Gr., nematos, thread) have been named, but many authorities now prefer Nemata for the name of this phylum. It has been estimated that if all species were known, the number might be nearer 500,000. They live in the sea, in freshwater, and in soil, from polar regions to the tropics, and from mountaintops to the depths of the sea. Good topsoil may contain billions of nematodes per acre. Nematodes also parasitize virtually every type of animal and many plants. Effects of nematode infestation on crops, domestic animals, and humans make this phylum one of the most important of all parasitic animal groups.

Virtually every species of vertebrate and many invertebrates serve as hosts for one or more types of parasitic nematodes. Nematode parasites in humans cause much discomfort, disease, and death, and in domestic animals they are a source of great economic loss.

Form and Function

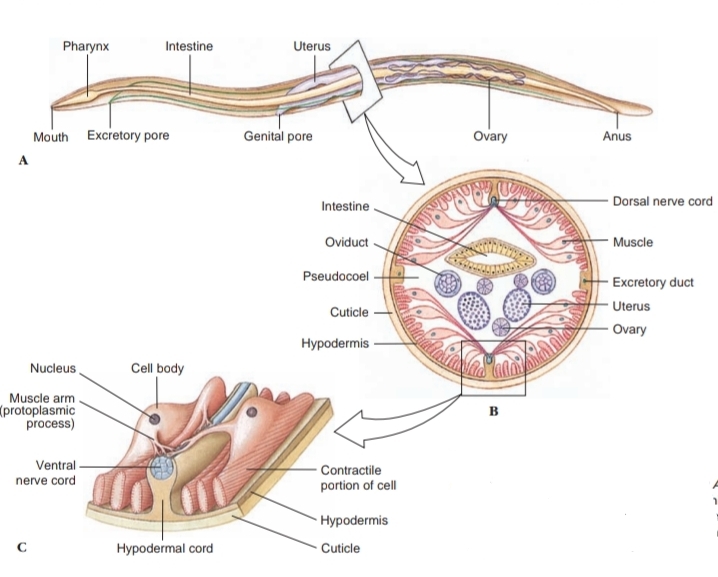

Distinguishing characteristics of this large group of animals are their cylindrical shape; their flexible, nonliving cuticle; their lack of motile cilia or flagella (except in one species); the muscles of their body wall, which have several unusual features, such as running in a longitudinal direction only, and eutely. Correlated with their lack of cilia, nematodes do not have protonephridia; their excretory system consists of one or more large gland cells opening by an excretory pore, or a canal system without gland cells, or both cells and canals together. Their pharynx is characteristically muscular with a triradiate lumen and resembles the pharynx of gastrotrichs and of kinorhynchs. Most nematode worms are less than 5 cm long, and many are microscopic, but some parasitic nematodes are more than 1 m in length.

Their outer body covering is a relatively thick, noncellular cuticle secreted by the underlying epidermis (hypodermis). This cuticle is shed during juvenile growth stages, which is one of the characters that places nematodes in the Ecdysozoa. The hypodermis is syncytial, and its nuclei are located in four hypodermal cords that project inward. Dorsal and ventral hypo-dermal cords bear longitudinal dorsal and ventral nerves, and the lateral cords bear excretory canals. The cuticle is of great functional importance to the worm, serving to contain the high hydrostatic pressure (turgor) exerted by fluid in the pseudocoel and protecting the worm from hostile environments such as dry soils or the digestive tracts of their hosts. The several layers of the cuticle are primarily of collagen, a structural protein also abundant in vertebrate connective tissue. Three of the layers are composed of crisscrossing fibers, which confer some longitudinal elasticity on the worm but severely limit its capacity for lateral expansion.

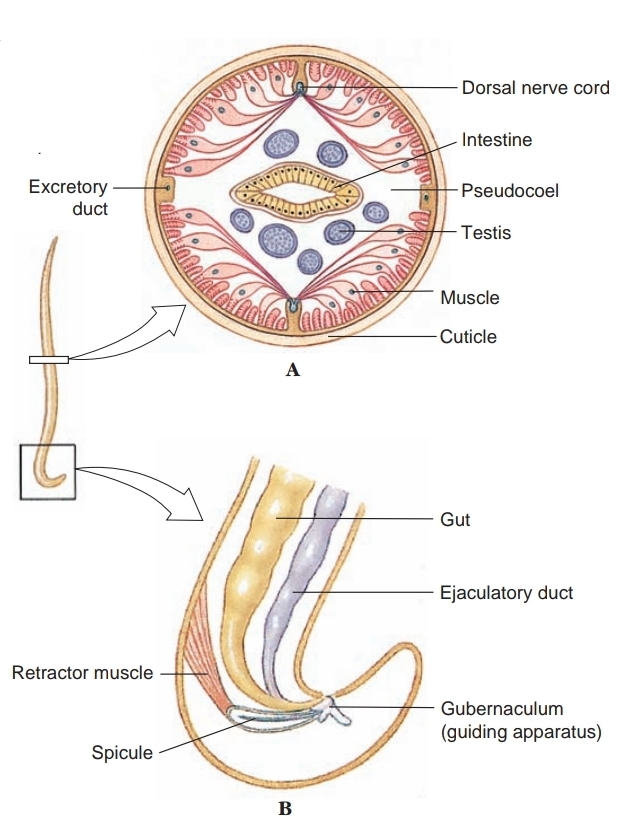

Body-wall muscles of nematodes are very unusual. They lie beneath the hypodermis (epidermal syncytium) and contract longitudinally only. There are no circular muscles in the body wall. The muscles are arranged in four bands, or quadrants, separated by the four hypodermal cords. Each muscle cell has a contractile fibrillar portion (or spindle) and a noncontractile sarcoplasmic portion (cell body). The spindle is distal and abuts the hypodermis, and the cell body projects into the pseudocoel. The spindle is striated with bands of actin and myosin, reminiscent of vertebrate skeletal muscle. The cell bodies contain the nuclei and are a major depot for glycogen storage in the worm. From each cell body a process or muscle arm extends either to the ventral or the dorsal nerve. Although not unique to nematodes, this arrangement is very unusual; in most animals nerve processes extend to the muscle, rather than the other way around.

The fluid-filled pseudocoel, in which the internal organs lie, constitutes a hydrostatic skeleton. Hydrostatic skeletons, found in many invertebrates, lend support by transmitting the force of muscle contraction to the enclosed, noncompressible fluid. Normally, muscles are arranged antagonistically, so that movement is effected in one direction by contraction of one group of muscles, and movement back in the opposite direction is effected by the antagonistic set of muscles. Recall how the longitudinal and circular muscles operate antagonistically in each annelid segment. However, nematodes do not have circular body-wall muscles to antagonize the longitudinal muscles; therefore the cuticle must serve that function.

As muscles on one side of the body contract, they compress the cuticle on that side, and the force of the contraction is transmitted (by the fluid in the pseudocoel) to the other side of the nematode, stretching the cuticle on that side. This compression and stretching of the cuticle serve to antago-nize the muscle and are the forces that return the body to rest-ing position when the muscles relax; this action produces the characteristic thrashing motion seen in nematode movement. An increase in efficiency of this system can be achieved only by an increase in hydrostatic pressure. Consequently, hydrostatic pres-sure in the nematode pseudocoel is much higher than is usually found in other kinds of animals that have hydrostatic skeletons but that also have antagonistic muscle groups.

The alimentary canal of nematodes consists of a mouth, a muscular pharynx, a long nonmuscular intestine, a short rectum, and a terminal anus. Food is sucked into the pharynx when the muscles in its anterior portion contract rapidly and open the lumen. Relaxation of the muscles anterior to the food mass closes the lumen of the pharynx, forcing the food posteriorly toward the intestine. The intestine is one cell-layer thick. Food matter moves posteriorly by body movements and by additional food being passed into the intestine from the pharynx. Defecation is accomplished by muscles that simply pull the anus open, and expulsive force is provided by the high pseudocoelomic pressure that surrounds the gut.

Adults of many parasitic nematodes have an anaerobic energy metabolism; thus, a Krebs cycle and cytochrome system characteristic of aerobic metabolism are absent. They derive energy through glycolysis and probably through some incompletely known electron-transport sequences. Interestingly, some free-living nematodes and free-living stages of parasitic nematodes are obligate aerobes and have a Krebs cycle and cytochrome system.

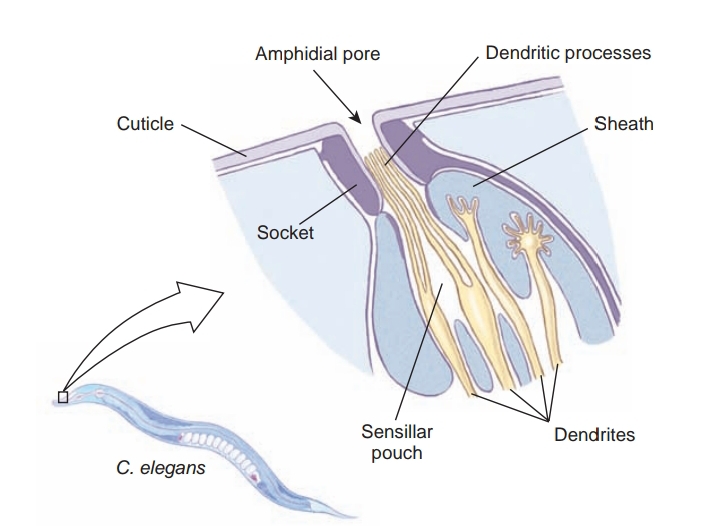

A ring of nerve tissue and ganglia around the pharynx gives rise to small nerves to the anterior end and to two nerve cords, one dorsal and one ventral. Sensory papillae are concentrated around the head and tail. The amphids are a pair of somewhat more complex sensory organs that open on each side of the head at about the same level as the cephalic circle of papillae. The amphidial opening leads into a deep cuticular pit with sensory endings of modified cilia. Amphids are usually reduced in nematode parasites of animals, but most parasitic nematodes bear a bilateral pair of phasmids near the posterior end. They are rather similar in structure to amphids.

Most nematodes are dioecious. Males are smaller than females, and their posterior end usually bears a pair of copulatory spicules.

Fertilization is internal, and eggs are usually stored in the uterus until deposition. Development among free-living forms is typically direct. The four juvenile stages are each separated by a molt, or shedding, of the cuticle. Many parasitic nematodes have free-living juvenile stages. Others require an intermediate host to complete their life cycles.

Useful External Links