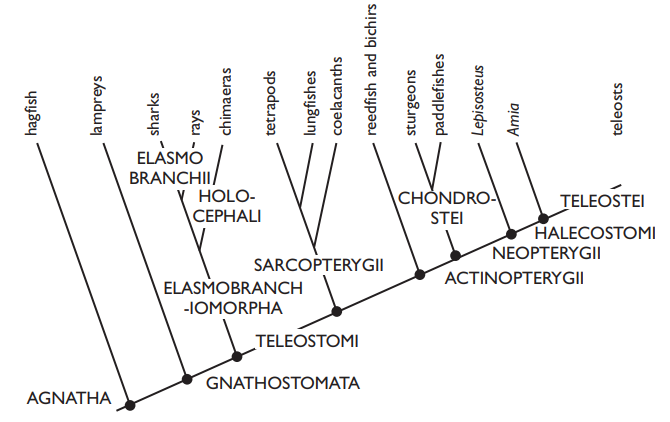

Holostei

Even fewer holosteans than chondrosteans survive today. The bowfin (Amia) of rivers in eastern North America, and seven species of garpikes (Lepisosteus and Atractosteus) from fresh and brackish waters of North and Central America, are all that remain. Garpikes are more primitive than Amia, and, as form the sister group to Amia and teleosts. However, both are much more like teleosts than chondrosteans. The skeleton is strongly ossified, the fins are more flexible, although with fewer fin rays than chondrosteans, and there is no spiracle. The heart has a large conus, and there is a reduced spiral valve in the intestine, but these primitive characters are overshadowed by such teleost features as the development of an eye muscle canal (myodome) in the floor of the skull, the loss of the clavicle from the pelvic girdle, and the freeing of the maxillary from the pre-operculum, strapping together the bones supporting the jaws.

Lepisosteus retains the thick rhomboidal ganoin-plated scales, which make the body relatively inflexible and reduce its fast-start performance. It is an ambush predator, hiding among weeds in shallow water, catching its prey with a sideways snap of the jaws. Since the giant tropical alligator gar (L. tristoechus) grows to 3.5 m, it is a very formidable predator. To achieve neutral buoyancy to enable garpikes to lurk in position, the airbladder has to be large (12% of body volume) to support the thick dense dermal amour. It is septated and is used also for respiration.

Amia is covered with thin teleost-like bony scales, and is overall much more like a teleost except for the reproductive system, for the ovary is not continuous with the oviduct: like elasmobranchiomorphs and chondrosteans, small eggs are shed into the body cavity before entering the oviduct. Cleavage is total, while in Lepisosteus it is meroblastic (partial only), as it is in teleosts.

Teleostei

Of all living fish, 96% are teleosts, an astonishing success since their radiation began in the Cretaceous, and they are very diverse. In size, they range from the largest specimen known of the giant European catfish (Siluris glanis) some 5 m long, although swordfish (Xiphias) and bluefin tunas (Thunnus thynnus) are heavier, to the smallest marine goby (Trimmatom nanus) at 8–10 mm, and the dwarf pygmy goby (Pandaka pygmaea), about the same size, from Philippine freshwaters. Some 10% of teleosts are 10 cm or smaller, and at least 80% between 10 cm and 1 m, so fitting into many different niches.

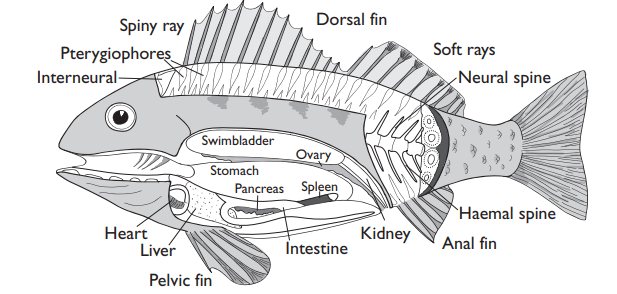

In comparison with holosteans, teleosts are generally more active, faster swimmers and more lightly built, with more flexible fins built from fewer fin rays. Living teleosts are the result of four main radiations, first clearly recognized (on morphological grounds) in the classical paper published by Greenwood and his colleagues in 1966. One has been far larger than the others. Of these four radiations, that in freshwater containing the electrolocating mormyrids and a few large fish, such as the arapaima (Osteoglossum), are regarded as the least advanced. The two other less advanced groups are the Clupeomorpha with the herrings, sprats, and anchovetas, and the Elopomorpha with eels, bonefish, and some deep-sea forms. Clupeomorphs all share good hearing, due to a complex link between the swimbladder and the ear. In some shads this even enables them to hear the ultrasonic hunting cries of dolphins. Elopomorphs, sometimes quite large fish such as the tarpon Megalops, all share the ribbon-like flattened leptocephalus larva, in some cases, as in the notacanth Aldrovandia, more than a meter long, but in most, as in Anguilla, shorter and willow-leaf shaped.

On the whole, the progressive changes leading to the largest and most derived group, the Euteleosts, from early teleost ancestors have been well summarized by W. B. Stout’s famous advice in designing the 1930’s Ford tri-motor aeroplane “simplicate and add more lightness.” From their paleoniscid ancestors, fishes with thick bony scales, and bones, similar to Polypterus or Lepisosteus, the modern Euteleosts have thinner scales, and lightened fin rays and skull bones. Although in most teleosts skeletal elements are well calcified, they are lightened by being built from a scaffolding of struts, quite unlike the dense cancellous bone of holosteans. Teleost skulls are like holostean skulls, except that the lower jaw has been simplified to just three components: dentary, angular and articular. Naturally, there are exceptions to such generalizations, as we might expect, for instance the huge ocean sun fish Mola (up to 1500 kg) has hardly calcified its skeleton at all, it feeds on a watery diet of salps and jellyfish, and many deep-sea fish have much reduced skeletal calcification to save weight. In exactly the reverse direction, ostracodont trunk or box fishes live inside a heavy bony cuirass, and many ictalurid catfish are heavily armored.

At the apex of the Euteleosts are the numerous Acanthopterygian species, so diverse in habit and form as to include small gobies; the huge sunfish (Mola); mackerel, and barracudas, and over 9000 perch-like fish.

In euteleosts, the heart has an elastic bulbus instead of the holostean contractile conus, and there are usually complex gut diverticula (pyloric ceca). Osteoglossids have a spiral valve, but it is lacking in higher teleosts.