Warm-water Fishes

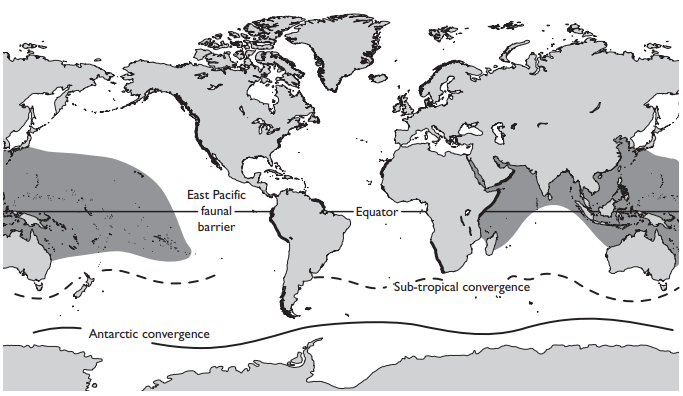

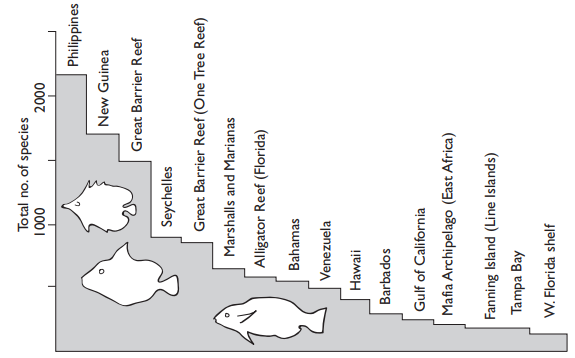

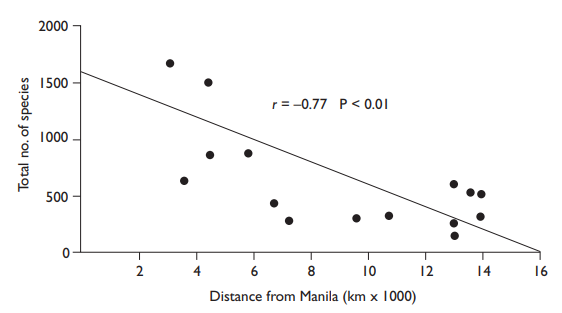

By far the greatest number (80%) of the 10 000 or so species of fishes in shallow seas live in warm temperate or tropical waters, most associated with coral reefs and atolls, in waters where mean temperatures during the coldest part of the year do not fall below 18°C. Coral reefs are widespread in the Indian and western Pacific oceans between latitudes 30°C north and 30°C south, and there are also large reefs in the Caribbean and around the West Indies. There is a striking difference in the number of species of coral fishes in different regions, from the richest central Indo-West Pacific reefs of the Philippines, New Guinea, and the Australian Great Barrier Reef to the less rich reefs around Florida where only 500–750 species live. The decline in species number, may reflect the Indo-West Pacific origin of the global coral reef fish fauna, divided into four main regions: Indo-West Pacific, Pacific American (Panamanian), West Indian, and West African.

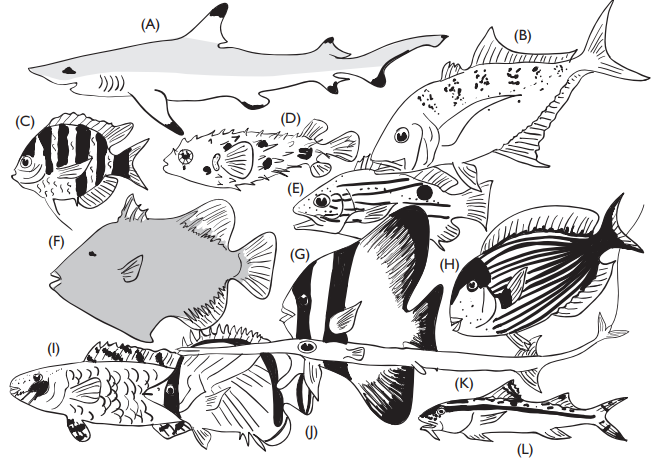

The eastern Pacific oceanic barrier (an east–west distance of some 4000–7000 km depending on where measured), between the Indo-West Pacific and Panamanian faunas, has been crossed by very few species. Some of these are large active swimmers such as the tiger shark (Galeocerdo), an important predator on seasnakes, and the spotted eagle ray (Aetobatis); others have made the crossing as long-lived pelagic larvae such as the leptocephali of the bonefish (Albula), and six species of moray eels, or the larvae of several species of puffers and triggerfishes. On the whole of the Great Barrier Reef 1300 species are known, but at its southern end (the Capricorn–Bunker group, which has been very well sampled, and is the best known region of the reef) only about two-thirds of these (859 species) occur. This impoverishment, however, seems primarily due to lowered habitat diversity (in the north, there are outer barrier reefs and inshore coastal reefs), and not to within-habitat diversity.

In contrast to the speciose Indo-West Pacific, other tropical regions contain fewer species. The Caribbean/West Indian region represents a secondary center of tropical biodiversity, sharing most of the same families as well as many genera with the Indo-West Pacific. These represent the descendents of a widespread tropical fauna that is believed to have lived in the warm, shallow tropical Tethys Sea stretching from what is now the western Pacific to what is now the eastern Pacific. Closure of the Red Sea land bridge about 18 mya divided this fauna into eastern (Indo-Pacific) and western (Atlantic and Eastern Pacific) components, which were further separated by the Messinian “salinity crisis” (8 mya) in which the Mediterranean basin was completely cut off from both the Red Sea and Atlantic becoming a hypersaline sea and possibly drying out completely. The opening of the Atlantic Ocean (10–32 mya) separated the geographically restricted and species-poor eastern Atlantic from the larger, richer western Atlantic.

Closure of the Isthmus of Panama about 3.5 mya led to the isolation of eastern Pacific populations and the subsequent evolution of pairs of closely related, and often virtually indistinguishable, geminate species on either side of the isthmus. The emergence of the isthmus was not a singular event, but perhaps as many as four distinct events, resulting in species pairs of varying antiquities.

Nearly all coral fishes are acanthopterygians, and many families such as gobies (Gobiidae), wrasses (Labridae), damsel fishes (Pomacentridae), butterfly fishes (Chaetodontidae), and squirrel fishes (Holocentridae) are represented globally at all coral reefs, although in each faunal area the species are largely different. On the Great Barrier Reef, 43% of all fishes are gobies, while wrasses and damsel fishes each comprise 23%, and butterfly fishes 8%.

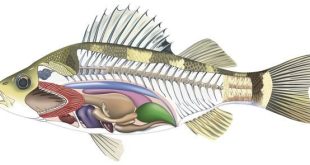

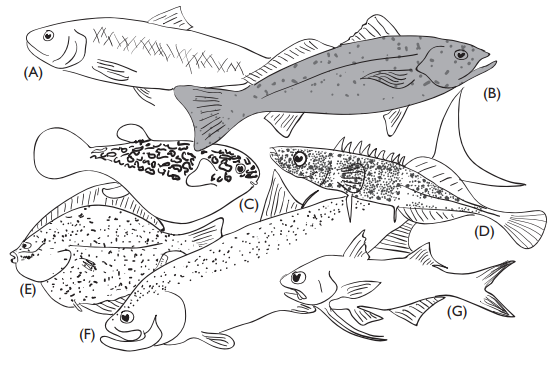

Coral fishes make their living in many specialized ways. Some are herbivores, cropping algae, or, like parrot fishes (Scaridae), scraping and biting off coral to obtain the algal symbionts. Others, such as puffer fishes (Tetraodontidae), boxfish (Ostraciontidae), gobies, and some damsel fishes, eat invertebrates, and these include the filefishes (Monacanthidae) and butterfly fishes that eat the coral polyps themselves, picking their food with their forceps-like mouths. Yet others prey on fishes, such as the trumpet fishes (Aulostomatidae) which stalk small fishes by swimming close to other non-predatory fishes. Maneuverability is important in the reef habitat, and, as a result, many coral reef fishes have abandoned normal oscillatory swimming except in emergencies and instead flap their pectoral fins (wrasse, parrot fish, and surgeonfishes (Acanthuridae)) or the dorsal and ventral unpaired fins (triggerfishes (Balistidae)), or undulate unpaired fins (seahorses, pipefishes, and trumpetfishes).

Most coral fishes are dazzlingly brightly colored, and change color during courtship as well as by day and night. During the night, large-eyed nocturnal feeders, such as squirrelfishes and the luminescent pempherids, emerge from their daytime hiding places, while day-feeding parrot fishes retire to sleep in mucous cocoons. As well as the brightly-colored and patterned coral fishes, there are also cryptically camouflaged ambush predators, such as carpet sharks (orectolobids), and frogfish (the Western Australian Batrachomoeus rubricephalus, as well as looking rather like a frog, croaks like one).

Fishes of Temperate and Cold Waters

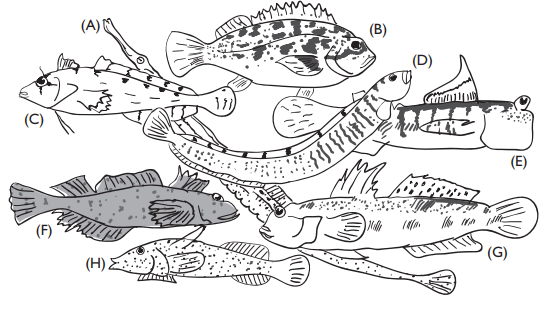

The coastal and shallow-sea fish fauna of temperate regions is much less rich in species than that of warm waters, since there are only around 1000 species in the temperate north Pacific, and many fewer in the temperate North Atlantic. Both regions contain members of the same families, such as the scorpion fishes (Scorpaenidae), kelpfishes (Clinidae), and eel-blennies (Lumpenidae), but in the north Pacific these families are more diverse, and this region also has some endemic families, such as the surf perches (Embiotocidae), and the greenlings (Hexagrammidae).

Although there are fewer species than in warmer waters, temperate and cold waters contain the most important food fishes, such as cod, pollock, and haddock (Gadidae), herrings and their relatives (Clupeidae), and the pleuronectid flatfishes such as plaice, soles, and flounders. Upwelling currents along coasts and mid-ocean convergences bring nutrient-rich deep water to the surface, supporting phytoplankton blooms nourishing the zooplankton on which fish feed. For example, off the Peruvian coast, upwelling is the basis for the fishery for the Peruvian anchoveta (Engraulis ringens), and oceanographic changes (the El Niño Southern Oscillation or ENSO) which reduce upwelling have catastrophic consequences for the fishery and for the seabirds that feed on the anchoveta. On the continental shelf, deeper nutrient-rich waters interact with surface water at fronts, which are regions of high productivity.

Temperate seas vary seasonally in temperature, much more than warm or polar seas which have a nearly constant temperature year-round. In consequence, phytoplankton and zooplankton abundance is seasonal. Thus, for example, Icelandic waters can vary from 0°C in February to 10°C in August, while the more temperate sub-Antarctic waters of the Southern Ocean are in the range 5–15°C. These waters lie between the Antarctic and Subtropical Convergences, and the former, where temperatures rapidly drop by 2–3°C, has long formed a barrier to exchange in sub-Antarctic and Antarctic regions. Once Antarctica had become fully separated from the other parts of Gondwanaland in the late Cenozoic (30–23 mya), the Antarctic circumpolar current decoupled sub-tropical waters from Antarctica, and this isolation permitted the wide adaptive radiation of notothenioid fishes comprising a species flock of over 100 species found only in the south polar ocean (Eastman and McCune, 2000). Molecular evidence indicates that notothenid fishes have been distinct for over 25 and perhaps 55 my (Bargelloni et al., 2000).

Notothenioids are found also on the southern New Zealand shelf and on the Patagonian shelf, perhaps relics of the severe cooling of the Southern Ocean in the Miocene and Pliocene which advanced the Convergence 3–7° north of its present mean position between 8 and 2 mya.

Apart from notothenioids, eel-pouts (Zoarcidae), and seasnails (Liparidae) also occur as coastal fishes in Antarctica, although these are species different from their nearest relatives across the Convergence in the coastal waters of the sub-Antarctic Southern Ocean that are found over the Chilean and Patagonian shelves. The commercially important gadoids, flatfishes (pleuronectids), and clupeids, such a conspicuous part of the fauna of north temperate seas, are poorly represented here, while such fish as the orange roughy (Hoplostethus) are presently still commercially important, although overfishing has produced a catastrophic collapse of the New Zealand and Australian stocks of these slow-growing, long-lived fishes to less than 20% of their pre-exploitation levels.

Estuarine Fishes

Like other estuarine animals, the fishes found in estuaries and river mouths are mainly euryhaline (salinity-tolerant) forms which can live in unstable surroundings, where salinity is variable and the waters are often turbulent and muddy, edged, in the tropics, by mangroves. At any one time, diversity may be low and dominated by just a few species, however, temporal partitioning of the estuarine environment by seasonal migrants, such as her-ring, sprat, eels, and salmonids, adds greatly to estuarine diversity. In temperate estuaries, typical fishes are grey mullets (Mugilidae), flatfishes such as flounders (Pleuronectectiformes), and shads (Alosa), while, in warm waters, many species of marine origin such as lutjanids, pomadasyids, catfishes, sciaenids, and threadfins (Polynemidae) are found in estuaries, supporting valuable fisheries such as that of the Niger estuary. Fishes of muddy estuaries may look rather like deep-sea fishes, with their long fin-rays and small eyes. The Bombay duck (Harpadon), of Indian estuaries, not only looks like a deep-sea fish, but is related to the deep-sea lizard fishes.

In regions of the world were evaporation exceeds freshwater inputs into enclosed coastal bays, hypersaline lagoons represent a special habitat for some estuarine species. The fish community of hypersaline lagoons is usually drawn from the more euryhaline species of nearby estuaries such as mullets, silversides, sciaenids, tilapias, and cyprinodontoids.

Intertidal Fishes

The intertidal zone is a demanding environment, where fishes are alternately buffeted by waves and isolated in pools or on mudflats. Some intertidal fishes, such as the mudskippers (Periophthalmidae), and leaping blennies such as Alticus kirki of the Red Sea, are truly amphibious, emerging from the water to graze on algal films on mud or rock in or above the splash zone. These fishes have remarkable behavioral and physiological adaptations to avoid (or withstand) desiccation and to regulate nitrogen excretion.

Most intertidal fishes, however, remain in the water, and, to avoid being washed away, generally are dense, small fishes (less than 20 cm), thin or flattened to hide in holes and crevices, or may have the pelvic fins modified into suckers. An interesting and obviously necessary behavioral feature of many intertidal fishes is their pronounced homing ability, particularly striking in pool-dwelling blennies that leap into the air to view the surrounding terrain. Intertidal areas are very important as nursery areas for young fishes, for example for young flatfishes in the Wadden Sea, and to avoid stranding, they move up and down as the tide ebbs and flows.

EazyBio: Educate, Elevate, Empower EazyBio: Educate, Elevate, Empower

EazyBio: Educate, Elevate, Empower EazyBio: Educate, Elevate, Empower