The digestive tract of fishes is divided into four regions: the foregut (esophagus and stomach, if present), mid-gut, hindgut, and rectum. The foregut begins at the posterior boundary of the gill cavity or pharynx and includes the esophagus, the stomach, when present, and the pylorus. Typically, the esophagus is a short muscular tube connecting the oropharynx with the stomach. Often the esophagus can expand to accommodate almost anything a fish can get in its mouth. In marine and euryhaline fishes such as tilapia, eel, and flounder, the esophagus also plays an important role in maintaining water balance, serving as a site for the absorption of water imbibed by the fish in order to offset osmotic loses to a hypertonic environment. Fishes of the order Stromateidae often possess pharyngeal sacs that may or may not be equipped with tooth-like projections. Many of these species feed on soft-bodied coelenterates.

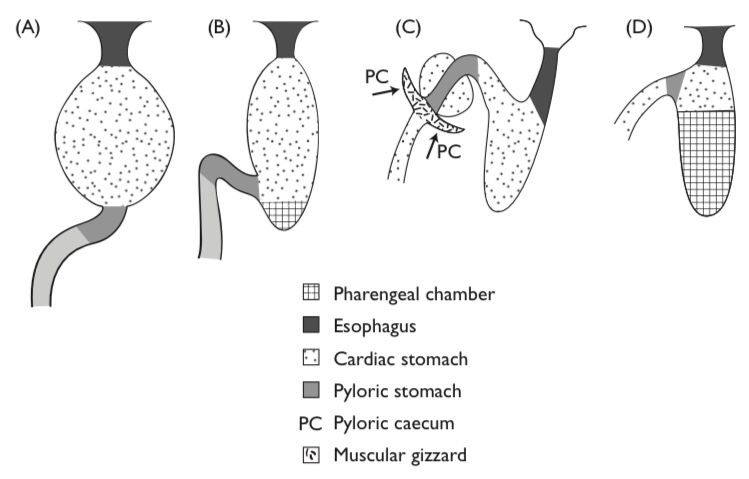

A stomach may be present or absent. In its simplest form, the stomach is an elastic sac that receives and stores food, and begins chemical digestion; however, in mullet, Corregonus, Sardinella, or Mormyrus – most of which are microphagous detritivores or herbivores part of the stomach may be modified into a gizzard-like structure .

Fishes which lack stomachs include Holocephalans, which typically feed on mollusks as well as some fish; lungfish, which are predatory on fish, mollusks, and arthropods, barnacle eating blennies, and a variety of herbivorous fishes. In most fishes the esophagus enters the stomach anteriorly and the intestine exits posteriorly. Typically, there is no anterior (esophageal or cardiac) sphincter, however, most fish possess a well developed pyloric sphincter that regulates the passage of partially digested food from the stomach. An interesting variation on this basic design is found in the Lake Magadi tilapia (Alcolapia grahami) that dwell in extremely alkaline waters (Bergman et al., 2003). In this species the intestine connects directly to the esophagus and the stomach at a three way junction formed rather like an upside down letter “T”. When the stomach contains food, the pyloric sphincter will close, permitting alkaline water to pass directly into the intestine, and thus preserving the acidic environment of the stomach. A some what similar situation is found in other tilapine cichlids in which the pyloric sphincter is located anteriorly in the stomach, but not in direct opposition to the esophagus.

The stomach is a site of protein digestion initiated by the enzyme pepsin. Hydrochloric acid (HCl) secreted by gastric glands provides proper pH for pepsin, and also serves as a chemical barrier to bacteria and parasites. It may also assist with the breakdown of hard, shelly materials. The stomachs of many fishes also exhibit chitinase activity, although whether this enzyme is secreted in the stomach or esophagus or both is not clear. The remainder of the gut is differentiated into regions, but what the physiological role is of each is not clear. Aside from the obvious roles in digestion and absorption of nutrients, posterior sections also play roles in salt and water balance and immunite.

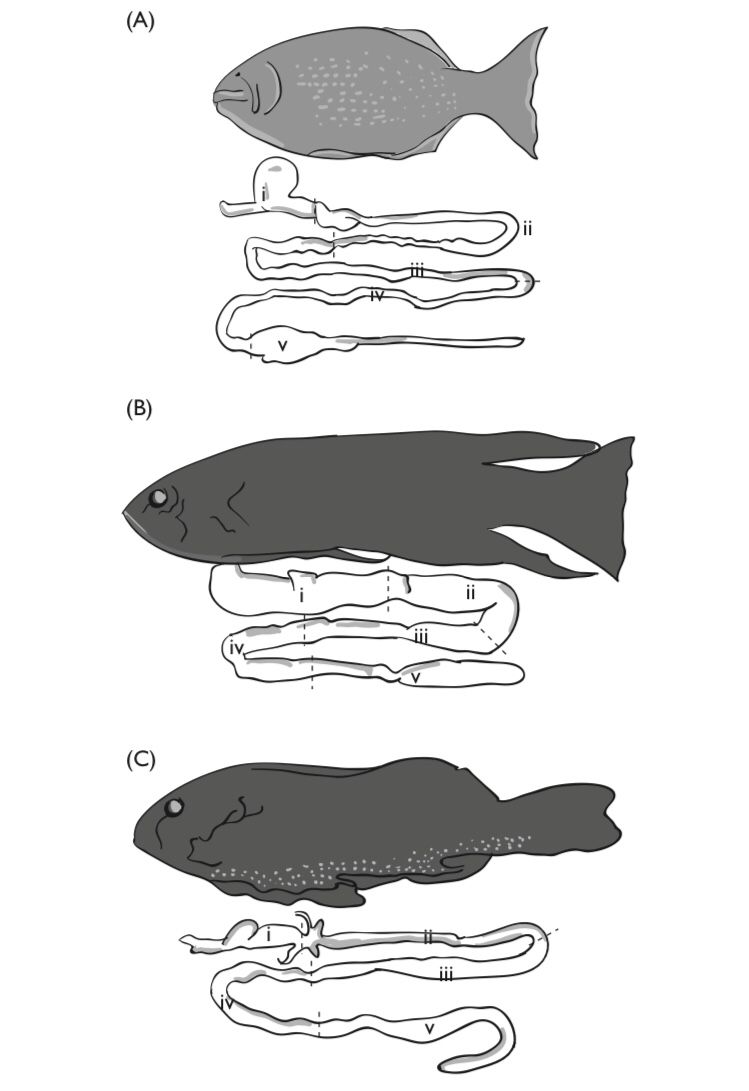

The mid-gut includes the intestines posterior to the pylorus, and often merges without anatomical distinction into the hindgut, although, in some fish, the beginning of the hindgut is marked by an increase in gut diameter. The mid-gut often includes a variable number (from zero to 1000) of pyloric caecae near the junction of the stomach and intestine. Pyloric caecae occur in fishes of almost every feeding variety and their function is not clear. It has been suggested that they serve to increase surface area or as sites for the absorption of certain nutrients (fats and waxes; Buddington and Diamond, 1986). They have been shown to contain digestive enzymes including pepsin which has a pH optimum of about 1.5–4, which is certainly not typical of intestinal PHs Horn, 1989). Pyloric caecae are always absent in fishes that lack stomachs. The mid-gut is typically the longest portion of the gut, ranging from less than one body length to over 20 body lengths and may be coiled into complicated loops (often characteristic for each species) when longer than the visceral cavity. The length and complexity of the mid-gut often provides a clue to the feeding habits of the species (de Groot, 1971), however this relationship is not infallible.

The remainder of the digestive tract may be differentiated into a hindgut and a rectum, and at the posterior end the hindgut exits the body cavity via the anus or cloaca; a chamber formed from infolded body wall, receiving both the anal and urogenital openings which occur in sharks, rays, and Sarcopterygians, but never in teleost fish or holocephalans. A pre-rectal ileorectal valve may be present, as in many teleosts, and some fishes also possess a single large hindgut caecum which may be used as a final site for digestion and absorption (Polypterus), fermentation of herbivorous materials or even as a respiratory chamber (Gee and Graham, 1978).

Like other animals, fish possess an array of digestive enymes by which large macromolecular nutrients are broken down into smaller molecules that can be assimilated. Most fish possess seven main digestive enzymes – trypsin, maltase, amylase, two +aminopepsidases (carboxypepsidase a, carboxypepsidase b), lipase, and alkaline phosphatase. Almost all the major enzymes are present in all fish regardless of their food habits, however, the relative concentration and activity varies according to food preference. Pepsin is localized in the stomach where it functions at optimum pHs between 1 and 4, while the others are found in the intestine at more alkaline pHs. The optimum pH for each enzyme varies with different regions and between different species. In general, the optimum pH for trypsin lies between 6.8–7.8, for carbohydrases 5–7, and for lipases the most alkaline > 7.8. There are two sources of enzymes for the mid-gut – the pancreas and the secretory cells in the gut wall. Since the pancreatic tissue is often diffuse and closely adhering to the liver, portal veins, and gall bladder, it is often difficult to determine the exact origin of many digestive enzymes. Many fish appear to produce amylase and other carbohydrases, but others rely on the activities of gut microflora to supply these enzymes.

Chitinase has already been mentioned as occurring in the stomach, but in some fish it is found only in the intestine where it is secreted by the pancreas. Absorption efficiencies of carnivorous and herbivorous teleosts differ significantly. In carnivorous species the energy absorption efficiency is around 80% (up to 97% for adult sea lampreys feeding on blood), and for herbivores much less, around 40–50%. The only elasmobranchs examined have been lemon sharks (Negaprion brevirostris), which have been found to have absorp- tion efficiencies up to 83%. It is interesting that lemon sharks and carnivorous teleosts should have similar energy absorption efficiency values, for the shark digestive strategy is very different to that of most teleosts. Thus, compared to teleosts, these sharks have a low rate of food intake (1% of body weight per day in the sandbar shark, Galeaspis), extended retention time, greatly increased surface area – with the spiral valve at the hinder end of the gut – and grow slowly.

EazyBio: Educate, Elevate, Empower EazyBio: Educate, Elevate, Empower

EazyBio: Educate, Elevate, Empower EazyBio: Educate, Elevate, Empower