Phylum Cnidaria (ny-dar´e-a) (Gr. knide, nettle, + L. aria [pl. suffix], like or connected with) is an interesting group of more than 9000 species. It includes some of nature’s strangest and loveliest creatures: branching, plantlike hydroids; flower like sea anemones; jellyfishes; and those architects of the ocean floor, horny corals (sea whips, sea fans, and others) and stony corals whose thousands of years of calcareous house-building have produced great reefs and coral islands.

The phylum takes its name from cells called cnidocytes, which contain organelles (cnidae) characteristic of the phylum. The most common type of cnida is the nematocyst described in the opening essay. Cnidocytes are formed only by cnidarians, but some ctenophores, molluscs, and flatworms eat hydroids bearing nematocysts, then store and use these stinging structures for their own defense. Cnidarians are an ancient group with the longest fossil history of any metazoan, reaching back more than 700 million years. They are widespread in marine habitats, and there are a few in fresh water. Cnidarians are most abundant in shallow marine habitats, especially in warm temperatures and tropical regions.

There are no terrestrial species. Colonial hydroids are usually found attached to mollusc shells, rocks, wharves, and other animals in shallow coastal water, but some species live at great depths. Floating and free-swimming medusae occur in open seas and lakes, often far from shore. Animals such as the Portuguese man-of-war and Velella (L. velum, veil, + ellus, dim. suffix) have floats or sails by which the wind carries them. Although they are mostly sessile, or at best, fairly slow moving or slow swimming, cnidarians are quite efficient predators of organisms that are much swifter and more complex.

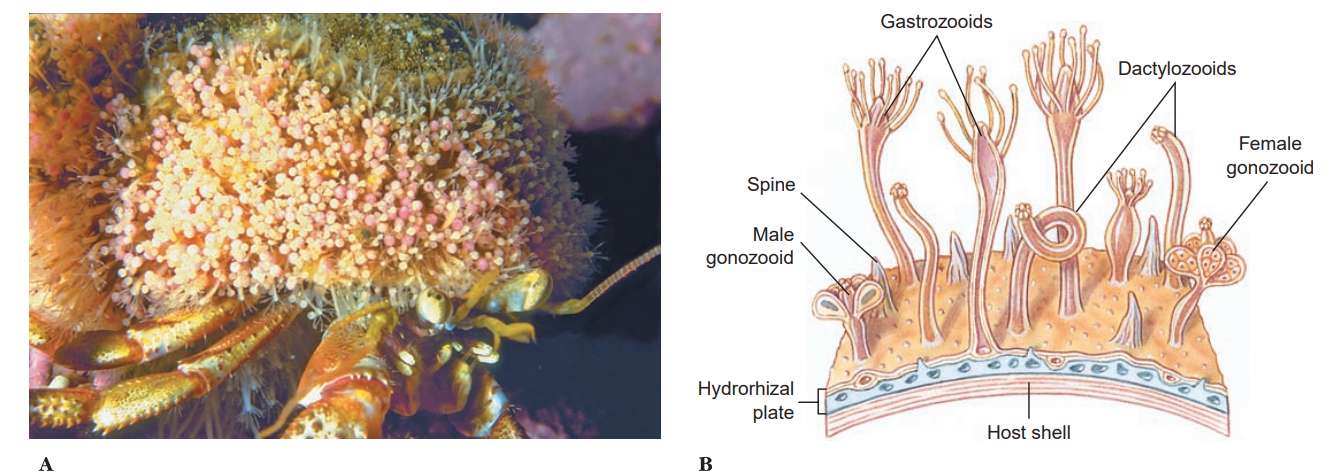

Cnidarians sometimes live symbiotically with other animals, often as commensals on the shell or other surface of their host. Certain hydroids and sea anemones commonly live on snail shells inhabited by hermit crabs, providing the crabs some protection from predators. Algal cells frequently live as mutuals in the tissues of cnidarians, notably in some freshwater hydras and in reef-building corals. The presence of the algae in reef-building corals limits the occurrence of coral reefs to relatively shallow, clear water where there is sufficient light for the photosynthetic requirements of the algae. These kinds of corals are an essential component of coral reefs, and reefs are extremely important habitats for many other species of invertebrates and vertebrates in tropical waters.

Although many cnidarians have little economic importance, reef-building corals are an important exception. Fish and other animals associated with reefs provide substantial amounts of food for humans, and reefs are of economic value as tourist attractions.

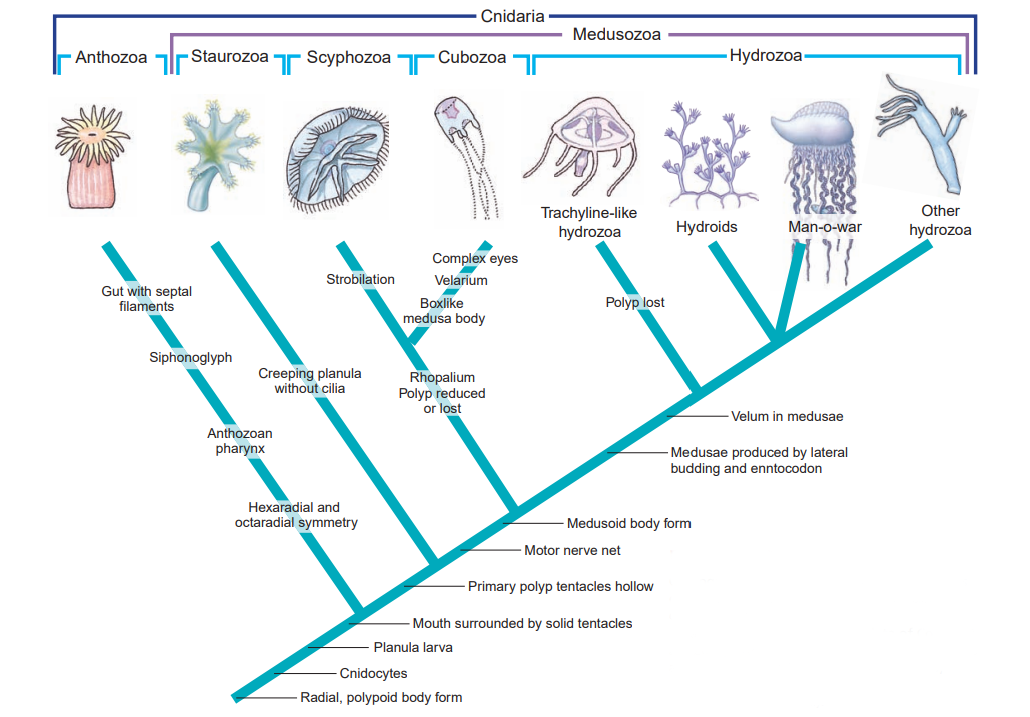

Precious coral is used for making jewelry and ornaments, and coral rock serves for building purposes. Four classes of Cnidaria were traditionally recognized Hydrozoa (most variable class, including hydroids, fire corals, Portuguese man-of-war, and others), Scyphozoa (“true” jellyfishes), Cubozoa (cube jellyfishes), and Anthozoa (largest class, including sea anemones, stony corals, soft corals, and others). A fifth class, Staurozoa, has been proposed because recent phylogenies show that stauromedusans do not belong within the Scyphozoa. These odd animals do not make medusae, but the polyp body is topped by a medusa-like region.

Useful External Links

- Phylum Cnidaria by University of Hawaii

- Phylum Cnidaria | Characteristics, Symmetry & Examples by Study.com

- Phylum Cnidaria by Pressbooks