Most animals move to search for food, but a sessile sponge draws food and water into its body instead. The entrance of water through myriads of tiny pores is reflected in the phylum name, Porifera (po-rif´ -er-a) (L. porus, pore, + fera, bearing). The sponge uses a flagellated “collar cell,” the choanocyte, to move water. The beating of many tiny flagella, one per choanocyte, draws water past each cell, bringing in food and oxygen, as well as carrying away wastes. The sponge body is designed as an efficient aquatic filter for removing suspended particles from the surrounding water.

Most of the approximately 15,000 sponge species are marine; a few exist in brackish water, and some 150 species live in freshwater. Marine sponges are abundant in all seas and at all depths. Sponges vary in size from a few millimeters to the great loggerhead sponges, which may exceed 2 m in diameter. Many sponge species are brightly colored because of pigments in their dermal cells. Red, yellow, orange, green, and purple sponges are not uncommon.

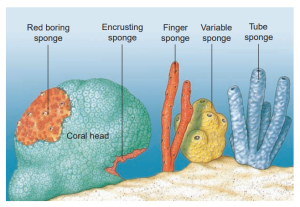

Although their embryos are free swimming, adult sponges are always attached, usually to rocks, shells, corals, or other submerged objects. Some bore holes into shells or rocks; others even grow on sand or mud. Some sponges, including the simplest, appear radially symmetrical, but many are quite irregular in shape. Some stand erect, some are branched or lobed, and others are low, even encrusting, in form. Their growth patterns often depend on shape of the substratum, direction and speed of water currents, and availability of space, so that the same species may differ markedly in appearance under different environmental conditions. Sponges in calm waters may grow taller and straighter than those in rapidly moving waters.

Many animals such as crabs, nudibranchs, mites, bryozoans, and fishes live as commensals or parasites in or on sponges. Larger sponges particularly tend to harbor a great variety of invertebrate commensals. Sponges also grow on many other living animals, such as molluscs, barnacles, brachiopods, corals, or hydroids. Some crabs attach pieces of sponge to their carapace for camouflage and for protection against predators. Although some reef fishes do graze on shallow-water sponges, most potential predators find sampling a sponge quite unpleasant. This antipredator effect is due to the sponge’s often-noxious odor and elaborate skeletal framework.

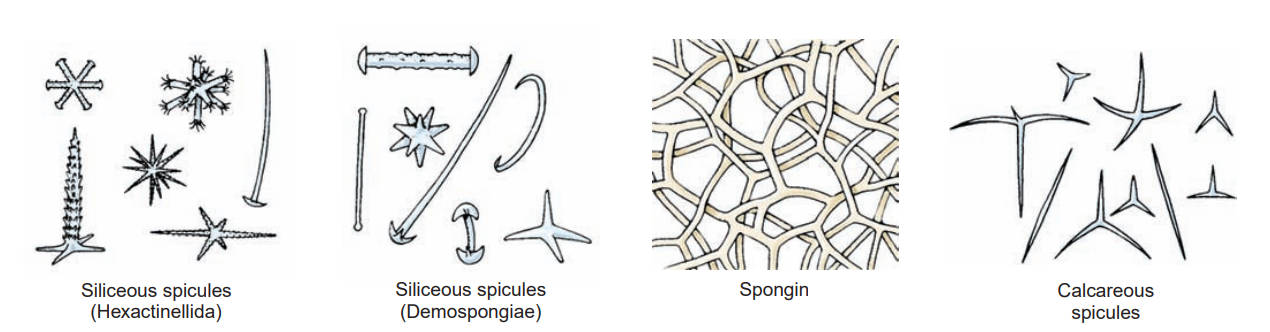

The skeletal framework of a sponge can be fibrous and/or rigid. When present, the rigid skeleton consists of calcareous or siliceous support structures called spicules. The fibrous part of the skeleton comes from collagen fibrils in the intercellular matrix of all sponges. One form of collagen is traditionally known as spongin. Collagen comes in several types differing in chemical composition and form (for example, fibers, filaments, or masses surrounding spicules).

Sponges are an ancient group, with an abundant fossil record extending back to the early Cambrian period and even, according to some claims, the Precambrian. Classification is based on spicule form and chemical composition. Living poriferans traditionally have been assigned to three classes: Calcarea, Hexactinellida, and Demospongiae. Members of Calcarea typically have spicules of crystalline calcium carbonate with one, three, or four rays. Hexactinellids are glass sponges with six-rayed siliceous spicules, where the six rays are arranged in three planes at right angles to each other. Members of Demospongiae have a skeleton of siliceous spicules, or spongin, or both. A fourth class (Sclerospongiae) was erected to contain sponges with a massive calcareous skeleton and siliceous spicules. Some zoologists maintain that known species of sclerosponges can be placed in the traditional classes of sponges (Calcarea and Demospongiae); thus we do not need a new class.

Useful External Links

- Phylum Porifera by toppr

- Phylum Porifera | Characteristics, Habitat & Examples by Study.com

- Phylum Porifera by LibreTexts

EazyBio: Educate, Elevate, Empower EazyBio: Educate, Elevate, Empower

EazyBio: Educate, Elevate, Empower EazyBio: Educate, Elevate, Empower